Architecture for Humanity

Nonprofit Helps Communities to Rebuild After Disasters

During the Kosovo refugee crisis in 1999, the husband and wife team of architect Cameron Sinclair and journalist Kate Stohr realized that not many architects were involved in rebuilding after the war. So the couple formed Architecture for Humanity, a not-for-profit design services firm originally located in New York City that helps communities to rebuild infrastructure devastated by human or natural catastrophes.

The firm began with an international design competition to build five- to 10-year transitional housing for refugees returning to Kosovo. Called simply “Architecture for Humanity,” the competition resulted not only in the building of five transitional housing prototypes but, by helping to raise more than $100,000 for fiscal partner, War Child USA, resulted in the building of schools, health clinics, and housing for families in war-torn areas.

Build Back Better Sendai

Fast forward to 2011. The organization, now headquartered in San Francisco, California, has completed more than 50 projects in Sri Lanka, Africa, India, Iran, and Mississippi after some of these regions were hit by hurricanes, tsunamis, and/or earthquakes. Among the 19 current projects is Build Back Better Sendai, in which Architecture for Humanity is working with local architects in Osaka and Kyoto to respond to those affected by the Sendai earthquake and tsunami. Architecture for Humanity will identify a local community group to rebuild and help to restore normalcy to the lives of those displaced.

“We continue to take on more projects in a variety of locations around the world and are revamping and expanding our chapter organization. We will continue to respond to disasters around the world, offering our expertise in rebuilding and community development, and seek to expand our network of partners, designers, and funders in the coming years.” Eric Kostegan, Volunteer Program Coordinator

The Sendai project, which already has been funded, will begin three months or so after partnerships are formed with Japanese architects and universities. A support team of all Japanese architects will be established, with Architecture for Humanity providing one or two staff members, including a design fellow (a volunteer selected by Architecture for Humanity for this specific project who receives a stipend) who will act as a facilitator during the design phase. The project is expected to be completed on the one-year anniversary of the disaster.

According to Eric Kostegan, Volunteer Program Coordinator, the turning point for Architecture for Humanity came in 2006, when Cameron Sinclair won the annual $100,000 TED (Technology, Entertainment, Design) prize. TED began in 1984 as a conference bringing together people from those three worlds. The TED Prize rewards innovations involving social issues.

Open Architecture Network

“The TED prize helped us expand and become well known for our work,” says Kostegan. “It also enabled Architecture for Humanity to launch its Open Architecture Network in 2007, which gained 10,000 members in its first year.” The Open Architecture Network is an online, open-source community dedicated to improving living conditions through innovative and sustainable design.

It is the first site to offer open-source architectural plans, drawings, and online viewing of CAD files. Architects can collaborate, manage projects remotely, and share design knowledge. The Open Architecture Network currently receives 50,000 unique visits monthly and had 30,000 registered users as of December 2010. It also provides a forum for running competitions with chapters and offers the Open Architecture Challenge. The theme for Open Architecture Challenge 2011 is “unrestricted access” and It focuses on the redevelopment of military facilities.

It is the first site to offer open-source architectural plans, drawings, and online viewing of CAD files. Architects can collaborate, manage projects remotely, and share design knowledge. The Open Architecture Network currently receives 50,000 unique visits monthly and had 30,000 registered users as of December 2010. It also provides a forum for running competitions with chapters and offers the Open Architecture Challenge. The theme for Open Architecture Challenge 2011 is “unrestricted access” and It focuses on the redevelopment of military facilities.

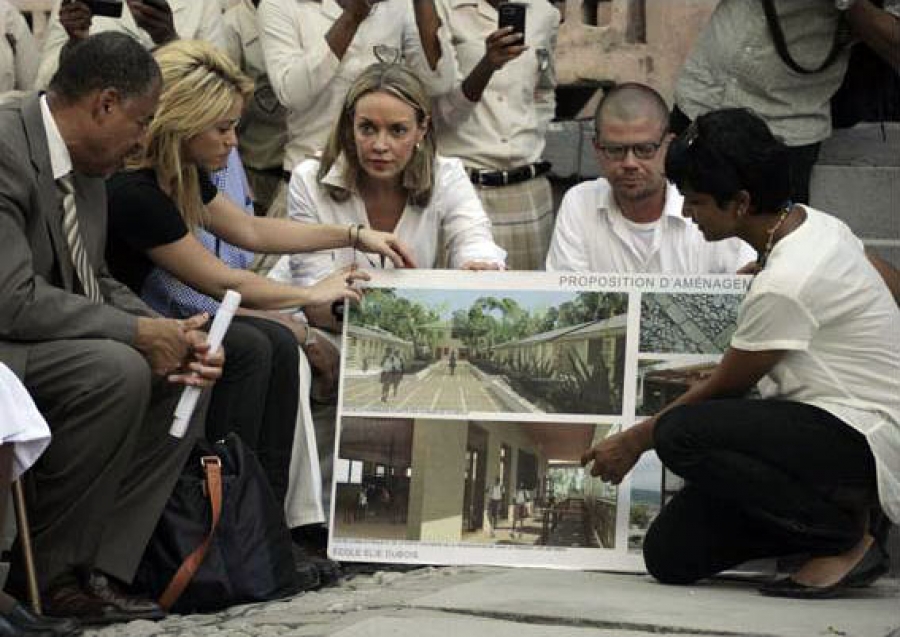

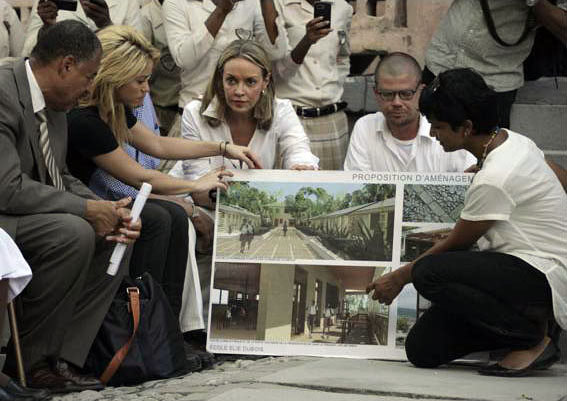

Despite Architecture for Humanity’s success (it has received 14 awards for its efforts and now has 70 chapters around the world), it has faced some challenges. “Usually we can tap into professional architects in the country we are helping,” says Kostegan.” "But in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake, this was not the case, and we had to fundamentally change the way we worked. We had to open an office in Haiti to coordinate the program that currently provides a staff of 12 and 12 rotating volunteers." This office is expected to remain open for five years.

For all of its projects, Architecture for Humanity uses 100% local and sustainable materials and community-based designs. For instance, a project for Navajo communities relied on tribal timber restoration, local concrete, and native-grown wheat straw bales. Collaboration with Navajo elders and other tribal members produced a range of culturally appropriate home designs.

Architecture for Humanity: Navajo Elder Strawbale Housing

-

Indigenous Community Enterprises staff with a straw bale hogan home.

-

Indigenous Community Enterprises and Enterprise Community Partners at substantial completion site meeting.

-

Kaibeto, Arizona, straw bale house ready for windows and final stucco.

-

Navajo straw bale hogan.

-

Navajo straw bale hogan landscape palette.

Architecture for Humanity also develops unique building materials to take advantage of local resources. One of these materials is compressed brick, which is used mostly in Africa (and, it is hoped, in Haiti) from local soil, which has the appropriate properties for making compressed brick.

In addition to responding to natural disasters, Architecture for Humanity focuses on underserved communities or places that are ignored. One such place is the village of Ipuli, located in the center of Tanzania, an East African country that has one of the highest infant mortality rates in the world (approximately 67 in 1,000 live births) and only two physicians for every 100,000 people. Many pregnant women die trying to reach the nearest clinic. Architecture for Humanity is building a medical center to serve the entire population of Ipuli, the services of which will include providing care to local mothers and their children and which willl also be the first rural health telecenter in Africa.

Architecture for Humanity is currently in strategic planning discussions regarding the future of the organization. “We continue to take on more projects in a variety of locations around the world and are revamping and expanding our chapter organization,” says Kostegan. “We will continue to respond to disasters around the world, offering our expertise in rebuilding and community development, and seek to expand our network of partners, designers, and funders in the coming years.”

Laurel Sheppard

Laurel M. Sheppard is an award-winning writer and editor who has authored several hundred articles related to ceramic materials technology and other engineering fields. She has a B.S. in ceramic engineering from Ohio State University and previously held editorial positions with Ceramic Industry, the American Ceramic Society Bulletin, Advanced Materials and Processes, and Materials Engineering. Her writing and editorial achievements have been recognized by the Society for Technical Communication, American Society of Business Press Editors, and Communications Concepts, Inc. She has also authored over a dozen market reports on various materials technologies and has written articles for IEEE’s Computer Graphics and Applications, Software Strategies, Native Peoples, SWE Magazine, and other publications.