Q & A with William Cary, Planner in Miami Beach

Buildipedia's interview with William Cary of the Miami Beach Planning Department sheds light on the city's development.

William Cary is the Assistant Director of the Miami Beach Planning Department. He is extremely knowledgeable about the city’s rich architectural history, and during his tenure, Cary has been influential in shaping the city into a magnet for notable modern architects. We spoke with him for our feature on the Evolution of Miami, but he provided so much interesting insight that we wanted to share more from that conversation.

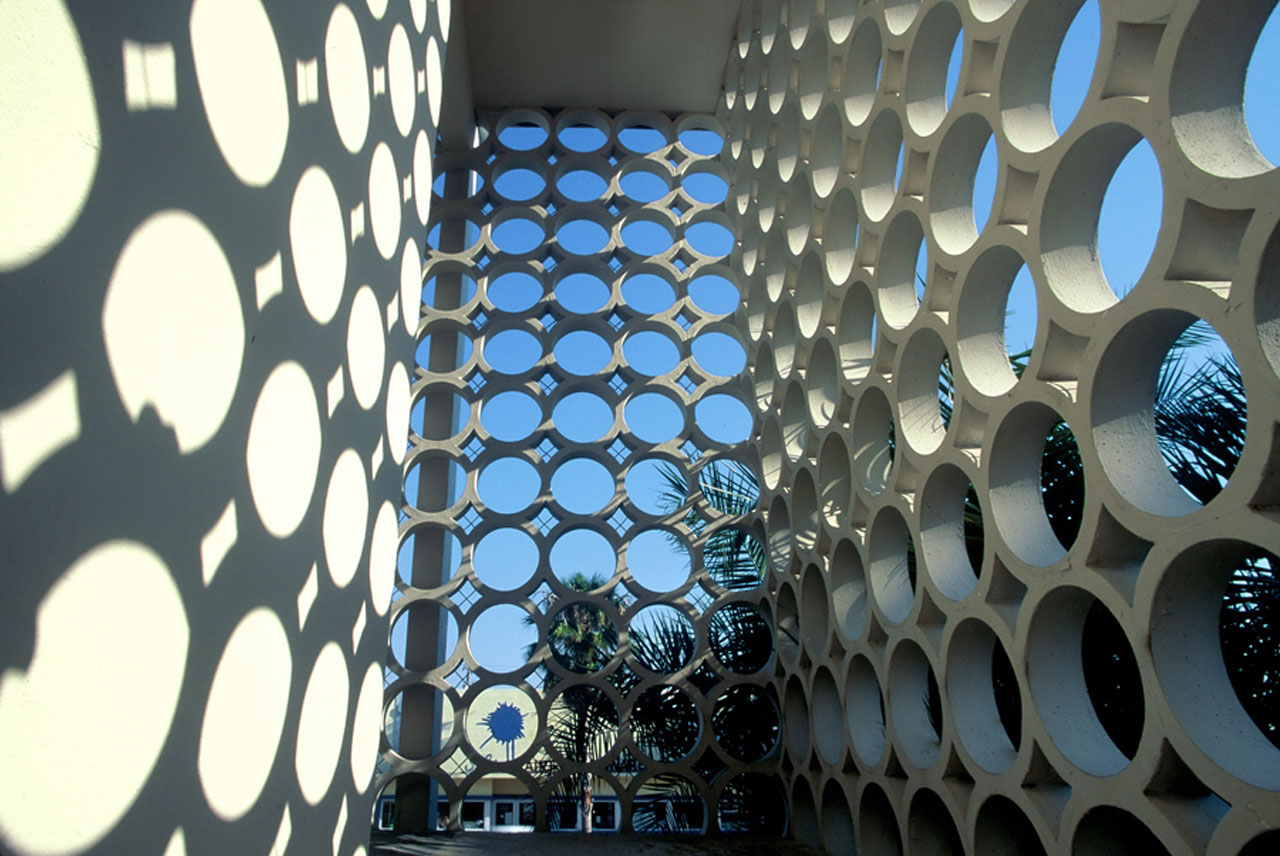

Image courtesy of Robin Hill ©

Image courtesy of Robin Hill ©

Can you provide us an overview of the history behind Miami’s architecture?

Miami Beach is essentially a 20th century city – it wasn’t incorporated until 1915. The key to the significance of its design is that it has evolved with the events of time, and every major economic event in America has changed the architecture of Miami Beach.

Initially, the architecture was vernacular and inexpensive, made from local materials like concrete block and stucco. Then Carl Fisher realized that, in order to market the concept of an urban, tropical city on the ocean, he needed to reference an architectural style that was regularly accepted and well known. Americans, especially the wealthy, associated value and romance with the Mediterranean Revival, and thanks to Fisher’s influence, it became the first definitive style for Miami Beach in the 1920s.

In 1926, a great hurricane wiped out half of the frame architecture of Miami Beach. Following that, a ship sank in the channel blocking the harbor entrance and delaying the shipping of materials for the rebuilding process. And then, of course, the great stock market crash of 1929 occurred, followed by the Great Depression – building Revival architecture became too expensive. Meanwhile, design influences from Europe – specifically the International Exposition of Modern Industrial and Decorative Arts in Paris – were influencing architects in New York, and some of them brought this influence when they relocated down to Miami Beach looking for work.

These architects began to define a new form of architecture, the Art Deco movement: basically a two-to-three story shoebox with masonry walls and wood framed floors. All of the design money was invested into the primary facade and lobby spaces. Elaborate materials like inlaid, rare stones and marbles and hardwoods were not affordable, so they adapted to what was locally available: keystone, etched glass and Vitrolite, concrete construction and terrazzo, creating textured and colorful surfaces. They also drew upon the nautical and marine themes, as well as natural flora and fauna, known as Nautical Deco or Tropical Deco. Many of our buildings from that period feature portholes and ships’ railings, which is totally appropriate for a seafront resort.

Then we evolved into the Streamline period, transitioning from symmetrical facades to those with rounded corners, echoing the evolution of speed: faster trains and ocean liners. Miami Beach found itself coming out of the Depression almost earlier than any other city thanks to tourism. The city streets, like Collins Avenue and Ocean Drive, became like stage sets and then tourists became the actors on the stage. That created the whole pedestrian ambiance – a wonderful collection of highly spirited, not deadly serious architecture. A tropical resort experience should be built with a certain joy, delight, and pleasure and relief from your everyday work-a-day experience.

World War II hit and manufacturing went into high gear to produce materials and weapons. After the war, the advanced use of materials such as aluminum was redirected into the domestic economy. Automobiles lessened reliance on traveling by ship and train and had a profound impact on the way resort architecture was designed; architects had to incorporate porte-cochčres and circular drives. In order to accommodate the returning troops, residential architecture became more affordable. It was also responsive to the tropical climate with exterior catwalks facing into courtyards, allowing for natural ventilation.

The next design period in Miami Beach was defined as Postwar Modern. The advent of the jetliner suddenly allowed middle-income Americans to vacation in Acapulco or London or Paris, which led to a total collapse of the tourism economy in Florida. In the midst of this severe decline, developers took advantage and bought up the cheap waterfront real estate. They built public housing projects of very low-grade architecture that were not sensitive to the environment and left a highly negative effect on the character of the historic areas of our city.

It was not until the Art Deco District was listed on the [National Register of Historic Places] in 1979 that there was a refocus on the success of the historic architecture of Miami Beach. The television show "Miami Vice" began using the city as a film set, painting buildings pastel colors, which caught the eye of the public. People said, “Wow, where is that?” It brought the fashion and advertising industries down here, so that forced the city to acknowledge that perhaps it should provide a little more protection to its historic resources. Before that, the city commission was opposed to preserving any older architecture; they wanted to demolish it all and build Palm Beach.

What is the criteria you’ve helped to develop for designating landmarked districts?

The first district to be dedicated since I started at the Planning Department in 1994 was the Ocean Beach Historic District, which included buildings of at least 30 years of age. By that point, the building can be identified as having made a significant contribution to the character of the city, based on the model of the New York City Landmarks Commission’s policy. The buildings in this district include the first wood framed building constructed in 1915, all the way through Postwar apartment buildings. That allowed us to establish the groundwork for every succeeding historic district designation.

You led efforts to gain approval for the Morris Lapidus Historic District (including the Fontainebleau and Eden Roc Hotels). Didn’t Lapidus receive a lot of criticism from other architects?

Objections arose to Lapidus during the 1950s. He always claimed that “I design for the people of my times,” and addressed their needs, as he would interpret them. He had an interesting range of clients with strong tastes, such as Ben Novack, who named the Fontainebleau after the chateau in France. He wanted the interiors to be French Renaissance Revival, but reinterpreted in a modern way. Lapidus’s challenge was how to define this in response to the current times, resulting in a thoroughly modern building that also responds to its tropical environment. He addressed the personal tastes of the client without compromising his own design values, but some people consider it kitsch.

Lapidus once met Frank Lloyd Wright, whom he admired as the only true American architect creating architecture of the time. Upon introduction, Wright asked him, “Have you done any works I’d be aware of?” and Lapidus responded that he had, and that Wright had recently visited the Fontainebleau. Wright said, “Of course, you have a talent that I believe is worth watching” and put his arm around his shoulder. Lapidus said it was the greatest moment in his life.

Lapdius’s work and other similar designs have recently been re-branded as MiMo – Miami Modern. How did that come about?

The term MiMo (pronounced “My-mo”) was only coined within the last four to five years by Randall Robinson and Teri D’Amico; the period is still referred to academically as Postwar Modern. "Art Deco" wasn’t even coined until around 1965, so these terms always come about after the fact. At the time, the architects are just designing modern architecture. The inventors of MiMo wanted to give it a catchy name that would stick in people’s minds.

Miami isn’t preserved as a time capsule by any means – there are so many new, exciting projects that have been built or are in the works. Tell us about how some of those are changing the landscape of the city.

Once our feet were firmly rooted to the ground in terms of protecting historic districts, we began to say, OK, now we have to go beyond the Art Deco and the Revival architecture to lead the design revolution of the city. We began attracting architects and firms such as Chipperfield, Michael Graves, Enrique Norten, Frank Gehry, and Herzog & de Meuron. For 1111 Lincoln Road, we worked closely with Herzog & de Meuron in trying to find a way to achieve their vision, for which we gave a large variance for the height. We recognized the importance of the architecture that was being proposed; the form was not an enclosed mass, but rather an urban sculpture that defines the entrance to Lincoln Road. We were able to make the case that this variance is warranted. Thanks to this project and others, Miami is quickly becoming an exhibition hall and a destination for interesting tropical design.

What does the Planning Department ask of architects designing new projects in Miami Beach?

We’re not colonial Williamsburg, we’re not an ecological site, we’re a real, living breathing city that depends upon tourism as its primary source of income. Therefore, we must provide the finest pedestrian experience possible. To that end, new projects must include glass storefronts to provide a connection with the street, and incorporate interactive indoor/outdoor spaces. Private developers are required to invest fortunes in landscaping and must hire registered landscape architects. We’ve built upon the ongoing success of learning from the past and adopting strategies that have proved to work, while using a whole new design vocabulary.

A special thanks to Robin Hill for contributing to the content found in this article.

Be sure to stop by robinhill.net to see more of his photography.

Murrye Bernard

Murrye is a freelance writer based in New York City. She holds a Bachelor's degree in Architecture from the University of Arkansas and is a LEED-accredited professional. Her work has been published in Architectural Record, Eco-Structure, and Architectural Lighting, among others. She also serves as a contributing editor for the American Institute of Architects' New York Chapter publication, eOculus.

Website: www.murrye.com