Art Deco in Cincinnati: Union Terminal and Carew Tower

Video

A tale of two buildings, and an Art Deco heritage that almost didn’t happen in Cincinnati.

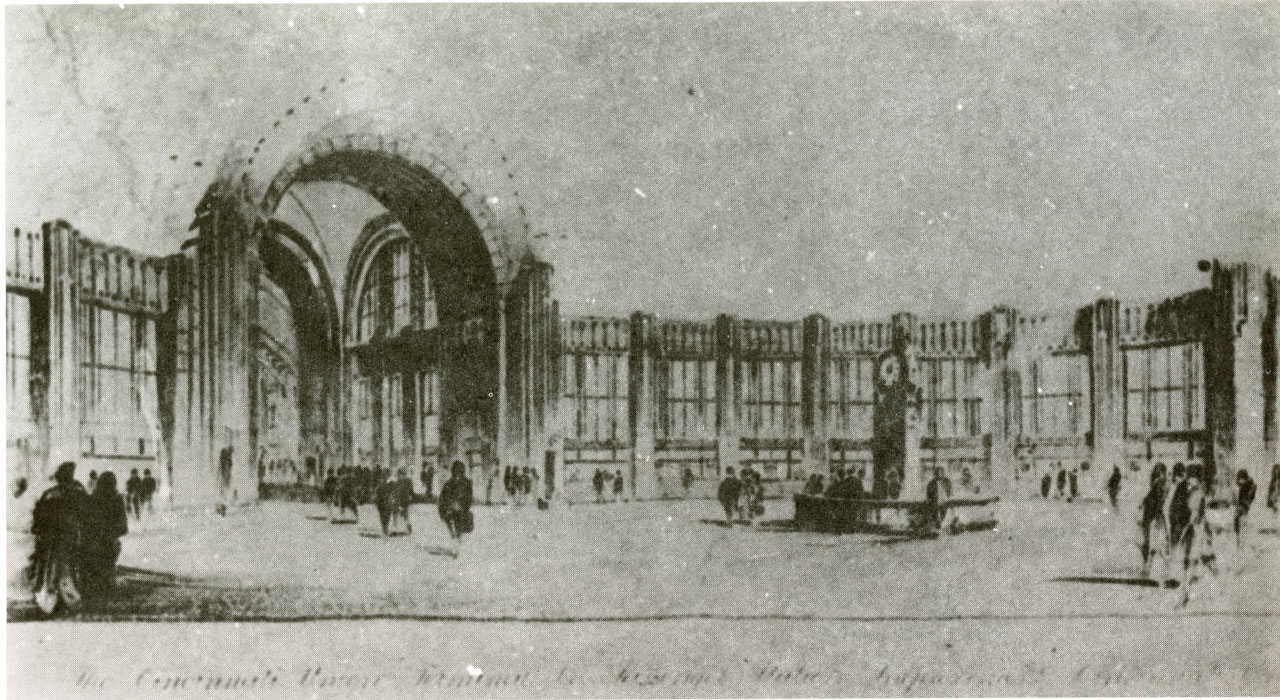

If you were to glance at an original 1929 sketch of Cincinnati’s Union Terminal, a masterpiece of Art Deco architecture and one of the last great train stations built in America, you’d be confused. That’s because the building was originally envisioned as neoclassical. “The sketches were almost gothic looking, and the design was thought to be cold,” says Scott Gampfer, director of the library and historic collections at the Cincinnati Museum Center. “The Cincinnati Union Terminal Company and the Cincinnati Public Works Department were not entirely satisfied with the look that was presented. They wanted to project the idea of modernity,” he says.

The design team, which included principal architect Roland A. Wank of Fellheimer and Wagner (a New York architectural firm that specialized in train stations) and Paul Philippe Cret, were asked to reimagine the massive 500,000 square foot building as Art Deco in 1931 (two years into construction) for two reasons.

First, Art Deco design was more in keeping with the cultural thrust of the day and the idea of modernity. After all, the Carew Tower, just a mile away in Cincinnati’s bustling downtown, was currently under construction, designed in an Art Deco style and slated to be the most impressive modern office/retail/hospitality complex in the region. Nine hundred miles away, in New York City, the Chrysler Building—still thought to be the best example of an Art Deco skyscraper—was about to become the tallest building in the city, for a time. In addition, Art Deco proved less expensive, because it made use of modern materials. And for a city grappling with The Great Depression, that looked mighty attractive.

By the time Union Terminal was completed in 1933, no signs of gothic remained. In the way it imagined space and the flow of people and cars, it was the most modern and forward-thinking train station in the region (and perhaps in the country, Gampfer says). With its sweeping, curvilinear shape and its extensive murals and decorations, it would come to represent the height of Art Deco.

Art Deco Origins

Art Deco dates back to a 1925 French exposition at Le Musee des Arts Decoratifs in Paris, organized as a display of the most modern designs from all around the world. “We saw a new attitude toward design. There were modern materials that embodied the excitement of modern life, with the infusion of machines into the forms of everyday objects,” says Aaron Betsky, architecture expert and director of the Cincinnati Art Museum. But there was also an emphasis on the natural world. “It was really the combination of natural forms with the streamlining and the machine look given by technology.”

In the neogothic era before Art Deco, what was popular was to make tall buildings look like cathedrals and apartment buildings look like larger versions of homes. “Art Deco stripped away those references for simpler, more geometric forms, whose edges had tight curves and were layered, as if the building was stripping itself down as it rose up,” Betsky says. It was progressive, energetic, and dynamic. The first wave of Art Deco expressed the optimism of the Jazz Age, but of course, that came crashing down in 1929. With the Great Depression, the streamlining that characterized Art Deco became even more prominent (especially by the mid-1930s), and the exuberance really came much more from the form, not the ornamentation.

The Art Deco Masterpiece That Almost Wasn’t

Cincinnati’s Union Terminal is certainly exuberant. In fact, to this day, it’s one of the most renowned Art Deco buildings in this country. However, what’s really remarkable is that it happened against the odds—and not just because of its neoclassical origin and rocky start. Not even because of the Depression. The odds were stacked against a building like Union Terminal ever existing because of the city itself.

The building of Union Terminal came only after decades of conflict about Cincinnati’s complicated train problem. With seven different railways serving Cincinnati, five train stations scattered over the city (including some in the flood plain of the Ohio River), and a small percentage of “through” trains (most were terminal and ended in Cincinnati), Cincinnati was a major bottleneck for both passengers and freight. Passing through Cincinnati meant you would often have to get off the train, get your bags, and be conveyed over to one of the other five stations to continue your journey, Gampfer says. The fate of freight was even worse—and certainly more complicated. “It was an embarrassment for Cincinnati. One railway publication even cautioned riders to avoid Cincinnati.”

After years of fruitless discussions, frustrated travelers, and arguments among all the parties involved -- not to mention a major world war which nationalized railroads -- things finally got moving in the mid 1920s. Even after it was decided that a central hub station would be built, there were still numerous arguments about where to put the station. For people who live in Cincinnati and know the Queen City to be overly cautious, this history isn’t surprising. It’s a city of many thwarted plans and agonizing discussions about where to locate things.

But in this case, being late to the party created a real gem. If Union Terminal had been built earlier, it wouldn’t have imagined space the way it does, and it wouldn’t have become the fine example of modernism that it is. It would be just another neoclassical train station: beautiful, but without many lessons for the modern world. Instead, it had the chance to become an innovative piece of architecture that would be studied by designers of modern travel stations.

A New Life as a Museum

Unfortunately, Union Terminal didn’t get to live a full life as the building it was designed to be. The peak year for train travel was 1944, according to Gampfer. The minute World War II was over, train travel started to decline, as people came to favor the automobile and the airplane. Union Terminal ceased being a train station in 1972, although it still serves an Amtrak line a few times a week. The concourses were demolished in 1974, and it fell into disrepair. The building served, for a time, as a shopping mall, although that venture was not successful. In 1990, it was reopened as Cincinnati Museum Center, and it currently houses three museums: The Cincinnati History Museum, The Museum of Natural History and Science, and the Duke Energy Children’s Museum. It also houses the Cincinnati Historic Library and Archives, as well as an OMNIMAX theater.

The building has been restored to its former Art Deco glory, with the great majority of murals being preserved, including the gorgeous mosaic murals in the rotunda, done by German-born artist Winold Reiss. “If the architects and planners from 1933 saw it now, I don’t think they’d be surprised or disappointed. They would think it was entirely appropriate and fitting that it be converted into a museum,” Gampfer says.

Art Deco Downtown

The Carew Tower, the other piece of Cincinnati’s Art Deco heritage, sits East of Union Terminal, in the heart of downtown Cincinnati. Envisioned by urban reformer John Emery (of Cincinnati) and designed by Walter W. Ahlschlager (of Chicago), Carew Tower was completed in 1930 and was Cincinnati’s tallest building until just a few years ago. Unlike Union Terminal, Carew Tower was supposed to be something special – and something surprising -- right from the very beginning. “It was revolutionary in combining many of the functions that made downtown Cincinnati so exciting in the 1920s and 30s: an urban arcade, hotel, public spaces, department, stores, and office space. All of those pieces came together as a fully worked out combination,” Betsky says. At 48 floors, the Carew Tower stood as a marker for the power of Cincinnati, and for everything wonderful that a mixed-use skyscraper could be. It wouldn’t be duplicated until 1933, when architect Raymond Hood’s RCA Building (now renamed the GE Building) opened in Rockefeller Center – and some say that the Carew Tower was a prototype for it.

The Carew Tower still functions in much the same way as it did 80 years ago. Visitors can’t help but notice the elaborately detailed interiors of The Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza—done in a French Art Deco style that has been restored to its original grandeur, with Brazilian rosewood paneling, indirect German silver-nickel light fixtures and magnificent ceiling murals. In fact, a good deal of the decorative work had been created in France specifically for the 1925 Exposition of Decorative Art in Paris. “It is a world of elegance—a real celebration of the human culture,” Betsky says.

Cincinnati’s Art Deco heritage is really a celebration of human culture too. It’s a story of plans working out and plans not working out—and how magnificent both can be.

Judi Ketteler

Judi Ketteler ( @judiketteler ) writes about creativity and design for web sites, magazines, and private clients. She's been published in Better Homes & Gardens, ElleDecor.com, Whole Living, and others. She's also the author of Sew Retro: A Stylish History of the Sewing Revolution + 25 Vintage-Inspired Projects for the Modern Girl (Voyageur Press, 2010). Find her at judiketteler.com.