Zaha Hadid Architects’ 57,519 m2 (approx. 619,129 sq. ft.) Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre, a mixed-use venue featuring a conference hall, library, and museum, is scheduled to open in September 2011 in the city of Baku, Azerbaijan.

The Setting

The Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre is one of many buildings that will be erected in Azerbaijan this year, and it is one of several projects exhibiting progressive design elements and cutting-edge engineering solutions.

The ambitious yet expressive nature of these new structures represents a move away from the country’s Soviet-dominated past and toward a national identity. The cultural centre, named in honor of the late Heydar Aliyev, National Leader of Azerbaijan, is located close to the city center. It is part of a larger redevelopment area and is expected to be a bellwether of the city’s intellectual and cultural life.

The Vision

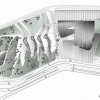

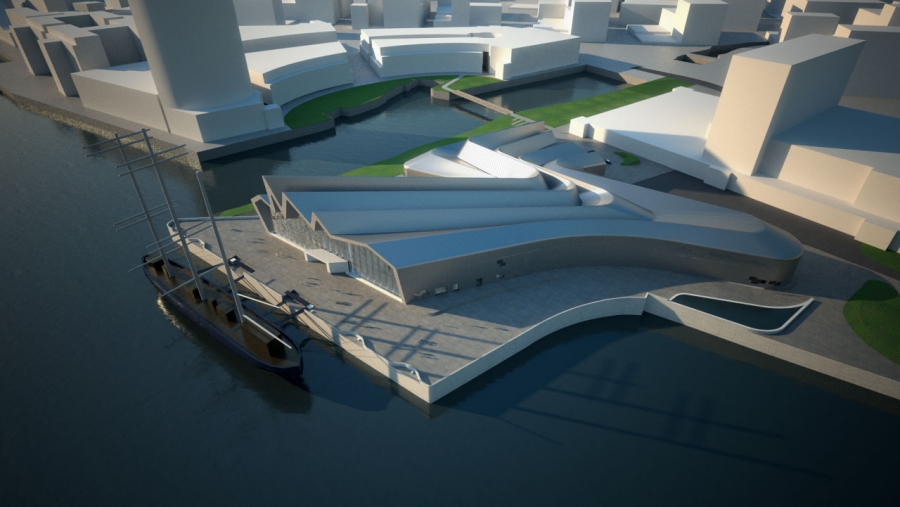

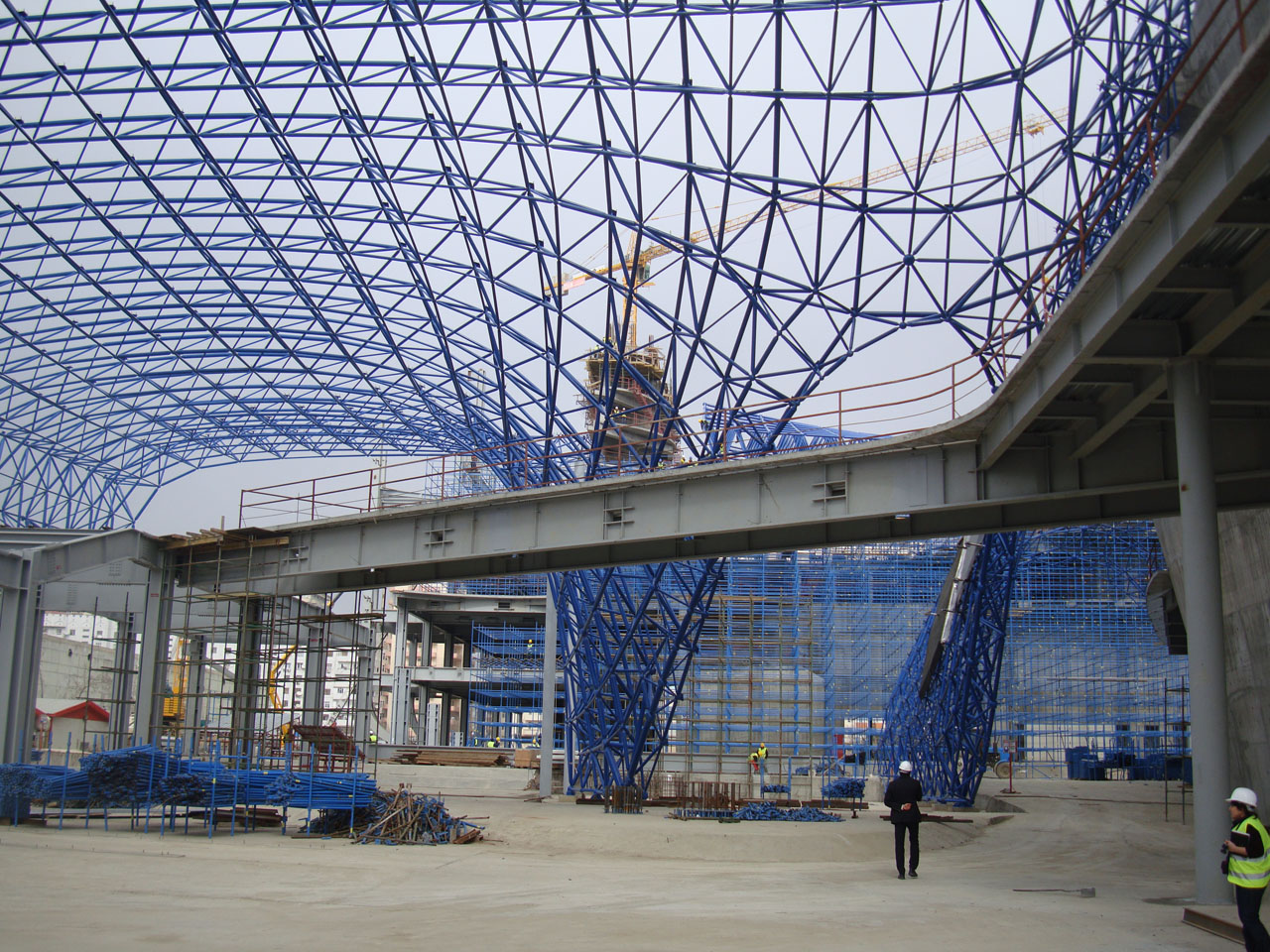

Zaha Hadid Architects created a building form that appears to emerge from the topography. The skin of the building – a single curving surface – rises, undulates, and wraps inward at its base to completely envelop the building’s various volumes. The curved surface allows a freedom of form that can simultaneously differentiate and unite the Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre's three distinct programmatic elements. Its inward curl is formed into stairways and ramps that connect the lower floors to mezzanine levels; other circulation paths also emanate from the curves of the building envelope. An elevated bridge connects the library to the conference hall.

“It is difficult in general to build something that extraordinary in a remote country where even very basic tools must be imported sometimes." Thomas Winterstetter, Werner Sobek

The Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre's conference hall contains three auditoriums. In order to accommodate the necessary inclined seating, this portion of the building protrudes into the cultural plaza. Here the mass of the structure undulates away from the wave-like peaks that define the other two zones of structure; at its edges it flows down to the walking surface of the plaza.

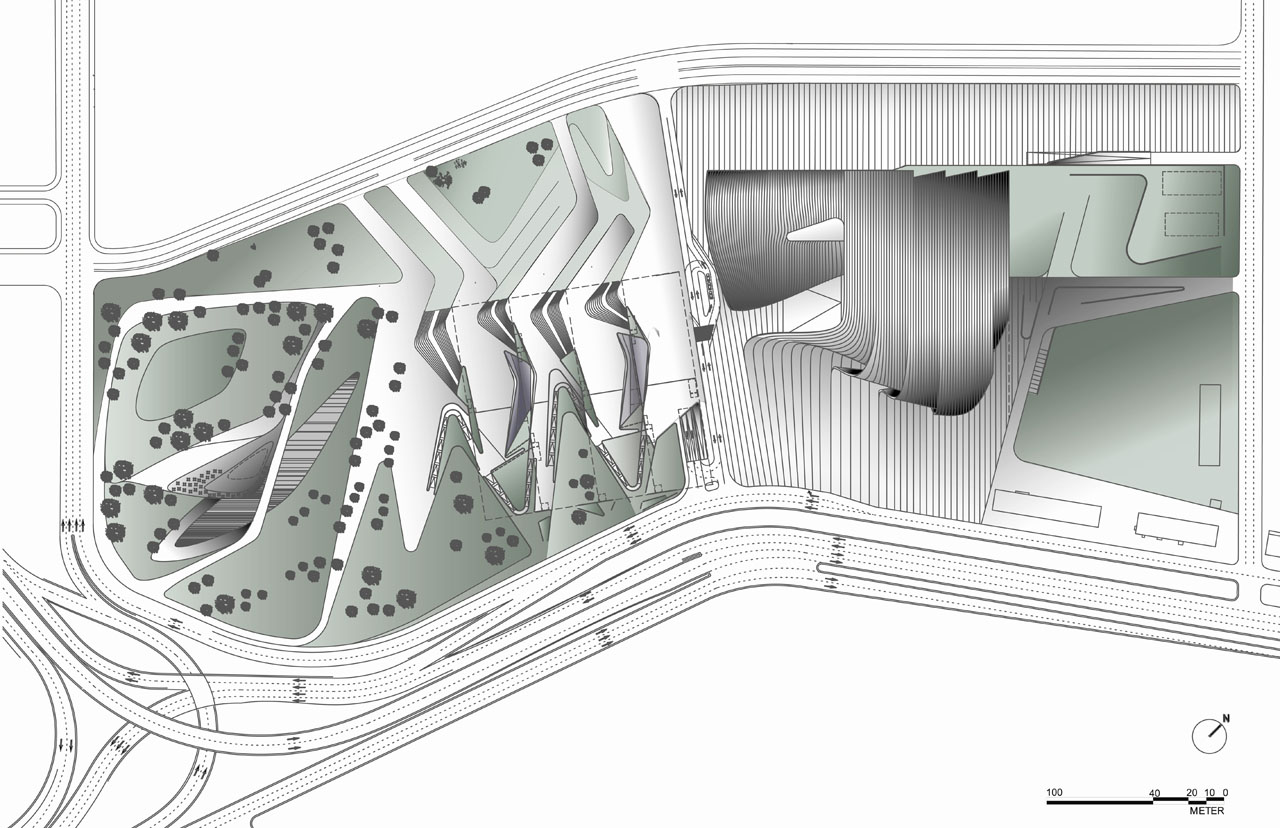

Site Plans

The Reality

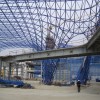

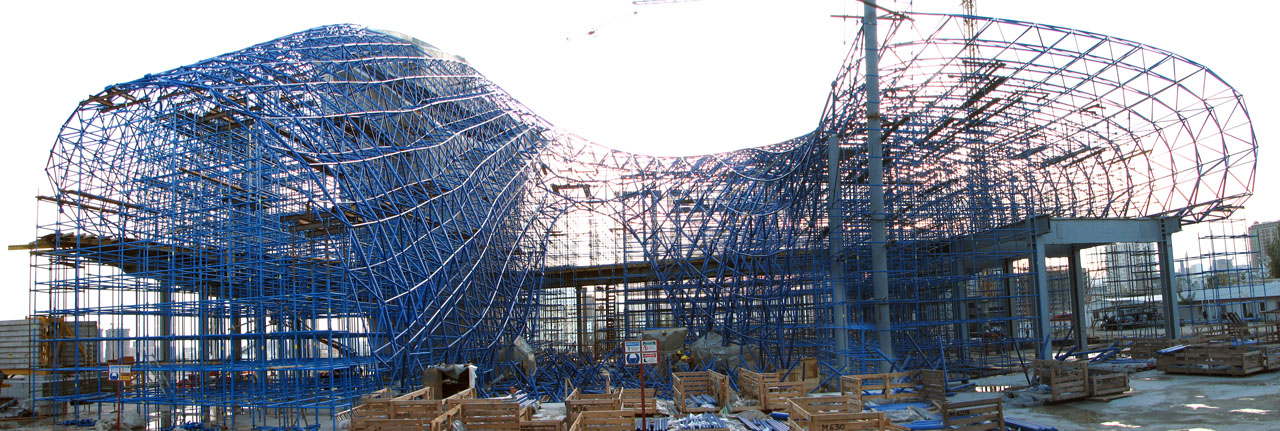

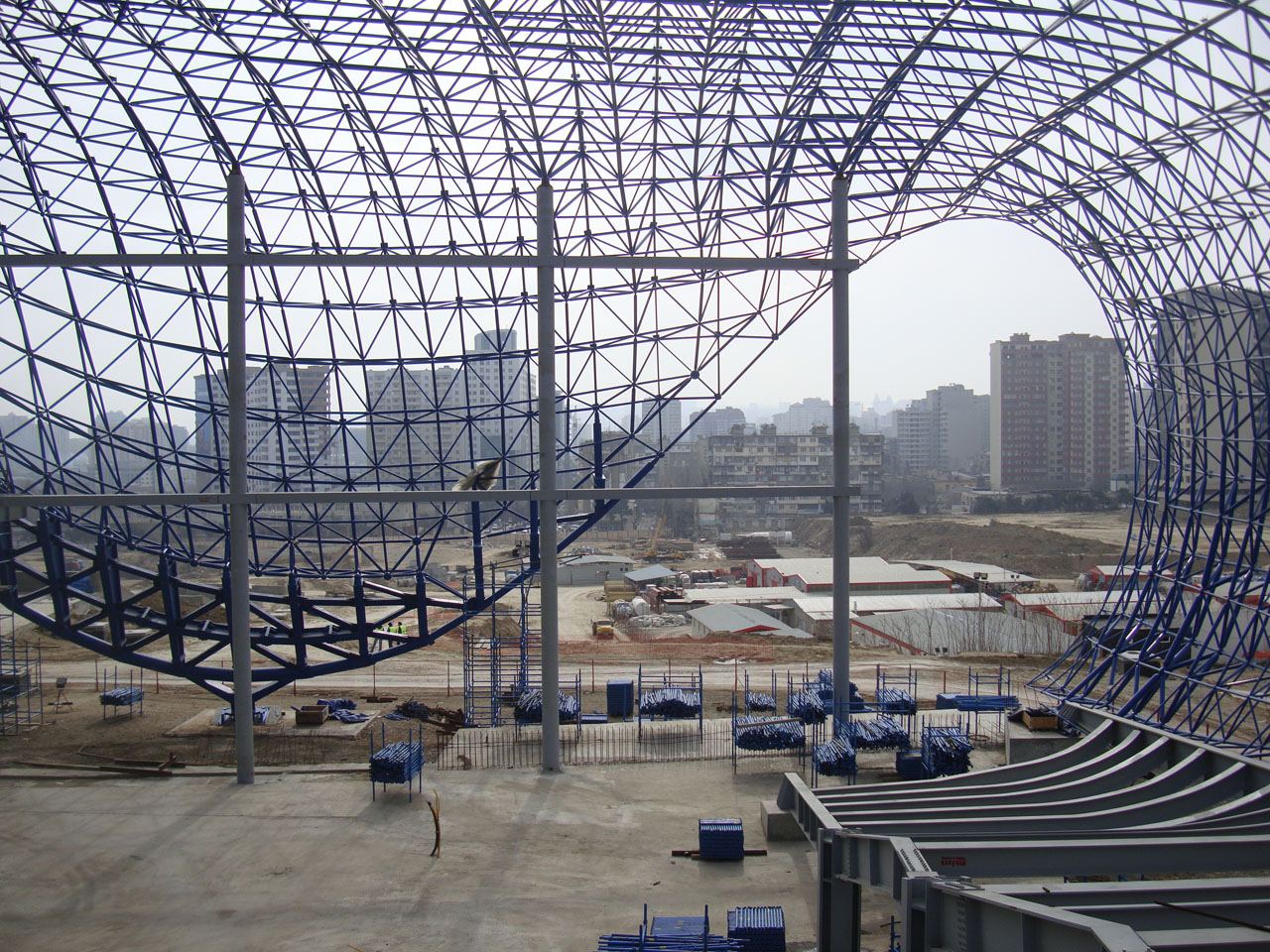

Zaha Hadid Architects’ vision of sublimity presented some very material challenges for the engineers and builders. The curve of the building’s exterior, meant to convey the aspirations and identity of the Azerbaijan people, needed also to function in more prosaic terms. It was necessary to construct a building that could seal out the elements and bear high wind and seismic loads without relying on interior support columns (which would have impeded the flow of space). Ultimately, a system was devised that utilized a space frame as its main structural element; the cladding is a curtain wall system comprised of various specially fabricated panels.

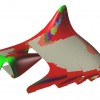

Early in the design process, engineers performed a mathematically based computer analysis. “It's good practice to do structural calculations for projects of that kind with a 3D nonlinear finite element analysis, including special loads like earthquake and high wind loads as present in Baku,” says Thomas Winterstetter of Werner Sobek, project engineer for the Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre. “We did the calculations with two separate full-model 3D finite element programs, in order to compare the results and not to rely on a single one.”

“We focused, for example, on easy-to-clean external cladding materials because of the heavy air pollution… There are oil refineries and such nearby, and the cladding is white. That's how glass fiber reinforced plastic (GFRP) came up, which is dirt-repellent itself. In general, all building systems are chosen to have high durability and a long lifetime and low maintenance efforts." Thomas Winterstetter, Werner Sobek

According to Winterstetter, the main structure of the Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre is a mix of reinforced concrete, steel frame structures, and composite beams and decks. The space frame is composed of a special steel tube-and-nodes system (a product of MERO-TSK International).

For aesthetic purposes, the cladding needed to give the building a monolithic appearance, not only to make it read as a continuous volume but also to accomplish the transition to the plaza surface. All visible seams needed to run parallel to one another, reinforcing the building’s wavelike design. The cladding material had to meet various practical considerations, such as UV resistance and light reflectivity. Maintenance was a big consideration, as well, notes Winterstetter. “We focused, for example, on easy-to-clean external cladding materials because of the heavy air pollution… There are oil refineries and such nearby, and the cladding is white. That's how glass fiber reinforced plastic (GFRP) came up, which is dirt-repellent itself. In general, all building systems are chosen to have high durability and a long lifetime and low maintenance efforts."

Building Envelope and Exterior Skin Panel Analysis

Glass fiber reinforced plastics (GFRP) and glass fiber reinforced concrete (GFRC) panels are the predominant materials used in the façade system. The panels are composed of “various layers of fine-grain high-performance white cement concrete, reinforced with fiber glass mats,” says Winterstetter. ”It's a very durable and resistive material which can be made very thin, only a few mm or cm, because there is no concrete cover needed, like for steel reinforcements.” By eliminating the need for steel reinforcing, the panels offer a lightweight construction method, and they can be individually molded to form the curved shapes required by the design. The panels are “cast into customized single-use molds. The molds are partly from CNC-cut 2D ribs (like a boat's hull) and partly from 3D-milled styrofoam blocks,” says Winterstetter.

Werner Sobek had to generate all of the production information associated with the exterior panels, so that they could be manufactured, then shipped to the site for installation by local workers. On site, each panel is lifted by crane, then negotiated into position by hand (which is possible due to the product’s light weight). The panels are screwed to fittings on a previously installed metal substructure. “There are about 15,000 panels, each with an individual curved geometry, in sizes up to a maximum of 1.5 m wide and 7 m long, none equal to another one. There are 40,000 m of 3D computer-generated substructure metal tubes underneath the panels, no tube equal to another one, perfectly matching the panels and their fixing positions,” says Winterstetter.

The Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre’s inner finish material also had to be shaped and fit onto a curved metal substructure, explains Winterstetter. Here the panels are made of cold-bent two-layer fiber-reinforced mineral boards. Resin panels were used for the flooring.

“It's good practice to do structural calculations for projects of that kind with a 3D nonlinear finite element analysis, including special loads like earthquake and high wind loads as present in Baku." Thomas Winterstetter, Werner Sobek

Although the building cladding was specially manufactured, no special fastener systems were required. “We used standard bolts and screws, standard drilled anchor systems for the concrete, and so on,” says Winterstetter. “It is difficult in general to build something that extraordinary in a remote country where even very basic tools must be imported sometimes.”

Building in remote regions is just another layer of complexity in an industry that is becoming more complex by the day. While architecture has always striven to express itself by exploring the limits of engineering practice, it is only the current generation that has seen such rapid redefining of those limits.

Kristin Dispenza

Kristin graduated from The Ohio State University in 1988 with a B.S. in architecture and a minor in English literature. Afterward, she moved to Seattle, Washington, and began to work as a freelance design journalist, having regular assignments with Seattle’s Daily Journal of Commerce.

After returning to Ohio in 1995, her freelance activities expanded to include writing for trade publications and websites, as well as other forms of electronic media. In 2011, Kristin became the managing editor for Buildipedia.com.

Kristin has been a features writer for Buildipedia.com since January 2010. Some of her articles include: