Adaptive Reuse: Borrowing from the Past

The design and construction of a building is always an arduous undertaking, even under the best circumstances. But when a project calls for the adaptive reuse of an existing structure, the challenges quickly multiply. Designers must bring older structures up to code, follow ADA guidelines and preservation standards, and work within the confines of outdated structural systems. Additionally, existing structures have already experienced the effects of time and decay, so extensive repair work is often in order. Considering all of these factors, design professionals who specialize in adaptive reuse often see their profession as somewhat of a labor of love. “The amount of work is out of proportion to the [architect’s] fee,” summarizes Carmi Bee, architect and president of RKT&B Architecture and Urban Design. Nevertheless, recent decades have seen a steady increase in the popularity of adaptive reuse.

An example of adaptive reuse can be found in the SoHo neighborhood of New York, NY, in the mid-20th century. Artists identified the area as a desirable place to live because its many warehouses and factories provided the large spaces that they needed to do their work, and rent was inexpensive. “Laws were passed allowing them to live there,” explains Bee, “and the idea caught on in places like Seattle, Portland, and Chicago.” The era of the artist’s loft was born.

“It’s a mix of historic guidelines and restrictions combined with creativity.” Elizabeth Wylie, Director of Business Development for FA+A on how adaptive reuse represents a complex combination of challenges and benefits.

Soon firms like RKT&B, which is based in New York, began to pioneer the broader movement of adaptive reuse. In 1977 the firm completed the renovation of the Turtle Bay Tower, a 26 story office and manufacturing facility which was converted into housing. The project gained national attention, winning a National Honor Award for excellence in architectural design from the AIA.

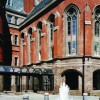

Similarly, Finegold Alexander + Associates, Inc. (FA+A), founded in 1960, saw the value in Boston’s historical building stock. With the completion of a new city hall in 1968, the city of Boston leased the old city hall to a private developer with the understanding that the character of the Second Empire style building would be maintained. F A+A converted the building into an office and restaurant space, but the exterior of the structure was left unchanged. This project also won an AIA National Honor Award for extended use. “Projects like this are now used as case studies for adaptive reuse,” says Elizabeth Wylie, Director of Business Development for FA+A.

A+A converted the building into an office and restaurant space, but the exterior of the structure was left unchanged. This project also won an AIA National Honor Award for extended use. “Projects like this are now used as case studies for adaptive reuse,” says Elizabeth Wylie, Director of Business Development for FA+A.

Borrowing from the Past

Transforming existing buildings into mixed use developments not only enhances the nation’s urban fabric in functional and aesthetic ways, but now adaptive reuse is becoming recognized as a very green practice, as well. “We started a history of building recycling,” says Dan Ricciarelli, an Associate Project Manager at FA+A.

In addition to providing recycling on a very large scale, older structures can usually be adapted to achieve energy efficiency and other green objectives. FA+A is currently working on a 62,575 sq. ft. (approx. 5,813 m2) Art Deco structure that originally functioned as the Cambridge Police Headquarters/V.F.W. and American Legion Halls. It is intended that the building will serve as office space for the Cambridge Housing Authority, and also provide office, classroom, and training space for several tenant non-profit groups. Says Rebecca Berry, FA+A’s project architect for the Cambridge Housing Authority adaptation, "Part of our approach is to expose the bones of the building, connecting the users with the historic structure, while putting back as few, as simple, and as sustainable of finishes as possible. Everything we put in is being selected from environmentally preferable products containing no chemicals contributing to offgassing, and manufactured nearby wherever possible. We are retrofitting the exterior masonry walls and roof with blown-in insulation. All of our faucets and toilets will be automatic and low flow, greatly reducing water use. The design will ready the historic structure for its second century as sustainable offices." Another way in which the designers are pursuing a healthy indoor environment is by reintroducing daylight into the building. They are removing a dropped ceiling which partially blocked existing windows, and are taking advantage of existing skylights.

“These are buildings that were designed for one use. To serve another use, they are never an ideal volume or dimension, so it is hard to do a layout to meet the new standards. The downside is that this takes more time, but the upside is that it always results in a unique floor plan." Carmi Bee, Architect and President of RKT&B

Adaptive reuse projects can also make sense from a broader economic standpoint. “These buildings can’t be replaced, so their market value goes up,” says Wylie. Also, substantial tax credits are available from the National Trust for Historic Preservation. There is a Federal Rehabilitation Tax Credit which “allows the owner of a certified historic structure to receive a federal income tax credit equal to 20% of the amount spent on qualified rehabilitation costs. There is also a 10% credit for older, non-historic buildings,” according to the Trust website. More than half the states also contribute rehabilitation credits.

Creative Thinking

Adaptive reuse represents a complex combination of challenges and benefits. “It’s a mix of historic guidelines and restrictions combined with creativity,” says Wylie.

Sometimes the tailoring of an old building type for a new user group can create a one-of-a-kind aesthetic. Another current FA+A project involves turning the old Salem Jail in Massachusetts into a residential complex. “This building has character and longevity, which are appealing. But historically it had a negative use. We turned it into a space with a positive use,” says Ricciarelli. Doing so involved the inventive reuse of an original architectural element: original jail cell bars were incorporated into the lobby.

RKT&B turned the former Sloane-Kettering cancer hospital into a 100-unit luxury condominium complex. The original part of the structure, an 1884 building on the National Register of Historic Places, is composed of an elegant spread of turreted, circular low-rise towers. “This was, in fact, a pragmatic shape. At the time the hospital was built, it was believed that cancer was caused by germs, and that germs lurked in corners. So, they built a building without corners for germs,” relates Bee. Today the hospital’s carefully crafted design provides an appealing complement to the project’s more contemporary twenty-seven story residential addition.

From a structural standpoint, old buildings can provide a difficult template in which to work. “These are buildings that were designed for one use. To serve another use, they are never an ideal volume or dimension, so it is hard to do a layout to meet the new standards. The downside is that this takes more time, but the upside is that it always results in a unique floor plan,” says Bee.

“Old buildings tend to lend themselves to office space,” says Ricciarelli, “We run into the most problems when we’re designing for a use wherein the dimension requirements are fixed by the state.”

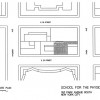

RKT&B encountered an especially difficult situation when they converted five floors in a Manhattan office building into a theme school for 500 intermediate and high school students. Called the School for the Physical City, the project required the installation of a gymnasium. “There were structural columns that couldn’t be removed from the space. So, we padded them well. Beyond that, well, they had to invent new games,” laughs Bee.

Still, sometimes the transition from one use to another does seem natural. “We had an example where an assisted living facility was adapted from an old hospital. The building lent itself to the new layout,” says Ricciarelli.

Bringing older buildings up to code is also a challenge, although sometimes building codes provide special solutions for historic structures. “Massachusetts has an aggressive code for older buildings, but there is, for example, leeway for old stairways,” says Ricciarelli. Often, new code-required stairs can be located in a less critical area of the historical structure. “Of course the old buildings were not built for seismic situations; now there is a rigid code dealing with seismic design,” continues Ricciarelli, “So sometimes it becomes interpretive, and engineers are involved to find a solution.”

On an adaptive reuse project, usually the most time and money is lost during construction, where workers often encounter the unknown. Both Bee and Ricciarelli describe this as finding a ‘surprise’ behind the wall. “You are flying blind with no radar,” says Bee, “And most of the time, there is no hidden treasure.”

It may be rare to find hidden treasure waiting inside the walls. But in the case of historic architecture, often the treasure is ‘hidden in plain sight.’

Kristin Dispenza

Kristin graduated from The Ohio State University in 1988 with a B.S. in architecture and a minor in English literature. Afterward, she moved to Seattle, Washington, and began to work as a freelance design journalist, having regular assignments with Seattle’s Daily Journal of Commerce.

After returning to Ohio in 1995, her freelance activities expanded to include writing for trade publications and websites, as well as other forms of electronic media. In 2011, Kristin became the managing editor for Buildipedia.com.

Kristin has been a features writer for Buildipedia.com since January 2010. Some of her articles include: