The Bertschi School, an independent elementary school in Seattle, Washington, has a history of emphasizing sustainability. In 2007, it was the first school in the state to have an elementary classroom building awarded LEED Gold certification. Now, with a new 1,425 sq. ft. science classroom scheduled for completion in November, the school is attempting to comply with an even more stringent green building rating system, the Cascadia Region Green Building Council’s Living Building Challenge.

Exterior Rendering

Credit: KMD Architects

Exterior Rendering

Credit: KMD Architects

According to the International Living Building Institute, the Living Building Challenge “defines the most advanced measure of sustainability in the built environment possible today and acts to diminish the gap between current limits and ideal solutions. This certification program covers all building at all scales and is a unified tool for transformative design, allowing us to envision a future that is Socially Just, Culturally Rich, and Ecologically Benign.”

"To make this work required a process, we had to sit with the teacher and figure out exactly what her electricity needs were for the classroom. Then engineers took that information and calculated the specific wattages." Chris Hellstern, KMD Architects, on the challenge of meeting net-zero energy requirements.

Currently in version 2.0, the Challenge seeks to promote buildings that achieve net-zero energy and water usage. It also advances progressive sustainability solutions such as urban agriculture. To earn Living Building status, buildings must demonstrate that they are meeting the rating system’s performance requirements for a full year of operation. If it succeeds, the Living Science Classroom will be the first Living Building in Washington State.

The Living Science Classroom was designed and built pro bono by a team of green building professionals in Seattle who united to form the Restorative Design Collective. Stacy Smedley and Chris Hellstern of KMD Architects initially organized the group.

Says Smedley, “We attended Cascadia’s ‘unconference’ in May 2009. The seminars on the Living Building Challenge got us excited, and we began brainstorming to see if there was any way we could get involved in designing one of these buildings. We knew we needed to find a small scale project -- smaller than the ones KMD usually does -- which would allow us to start building our knowledge.”

“At that same time, we went on a tour of the Bertschi School. Upon talking to the owner, we found out that they were planning on eventually adding a science classroom to the campus, and even had hopes of building a Living Building … and this at a time when the Living Building Challenge was not well known outside of the industry,” adds Hellstern.

It only took a few emails to colleagues to assemble the Restorative Design Collective. Together the team took the project from its conceptual phase through construction documents, making great strides in furthering the industry’s proficiency in deep green building practices.

To meet the Challenge’s requirement that buildings have a net-zero energy usage, the Living Science Classroom will use solar panels as a renewable energy source to supply all of the building’s energy needs.

“To make this work required a process,” says Hellstern. “We had to sit with the teacher and figure out exactly what her electricity needs were for the classroom. Then engineers took that information and calculated the specific wattages.”

Additional Reading

To follow some of the efforts that local and county governments are making with regards to living buildings and sustainable development in the Seattle area, check out the links below.

- Seattle City Council

- Results of a study on code and regulatory barriers performed jointly by the Cascadia GBC and the City of Vancouver, WA and Clark Count, WA

- Clark County's Sustainable Communities Pilot Project Ordinance

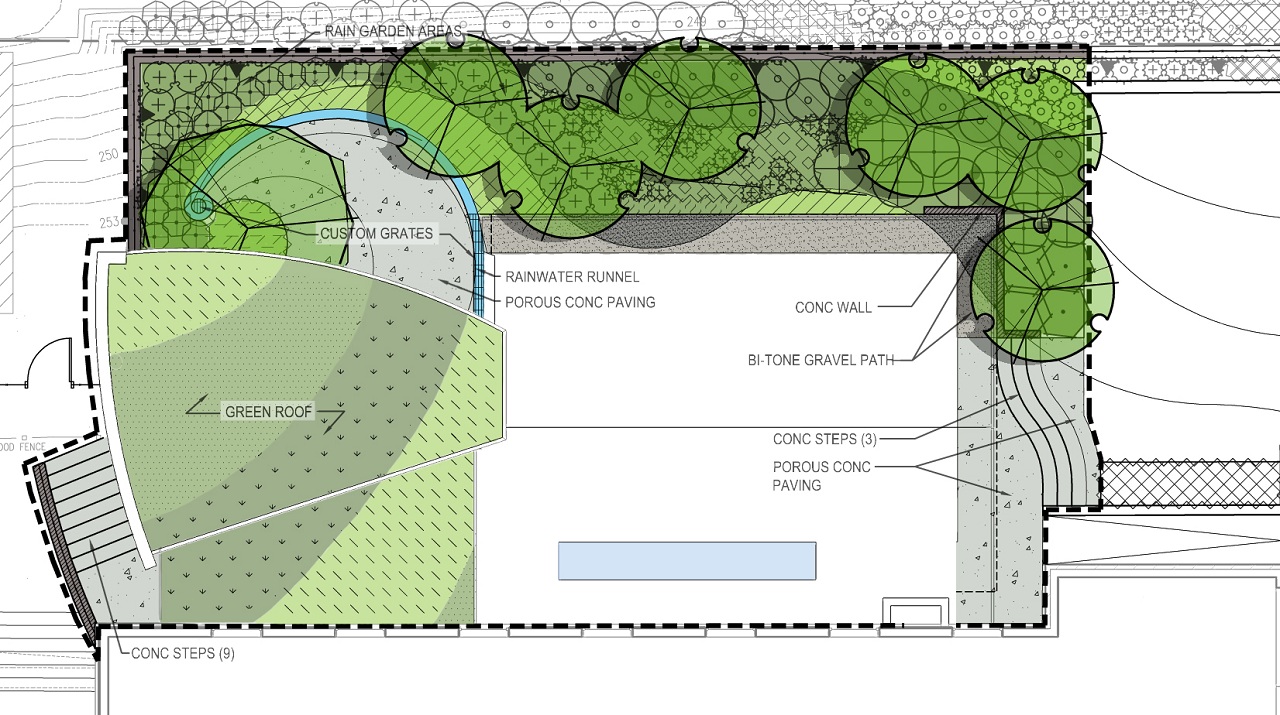

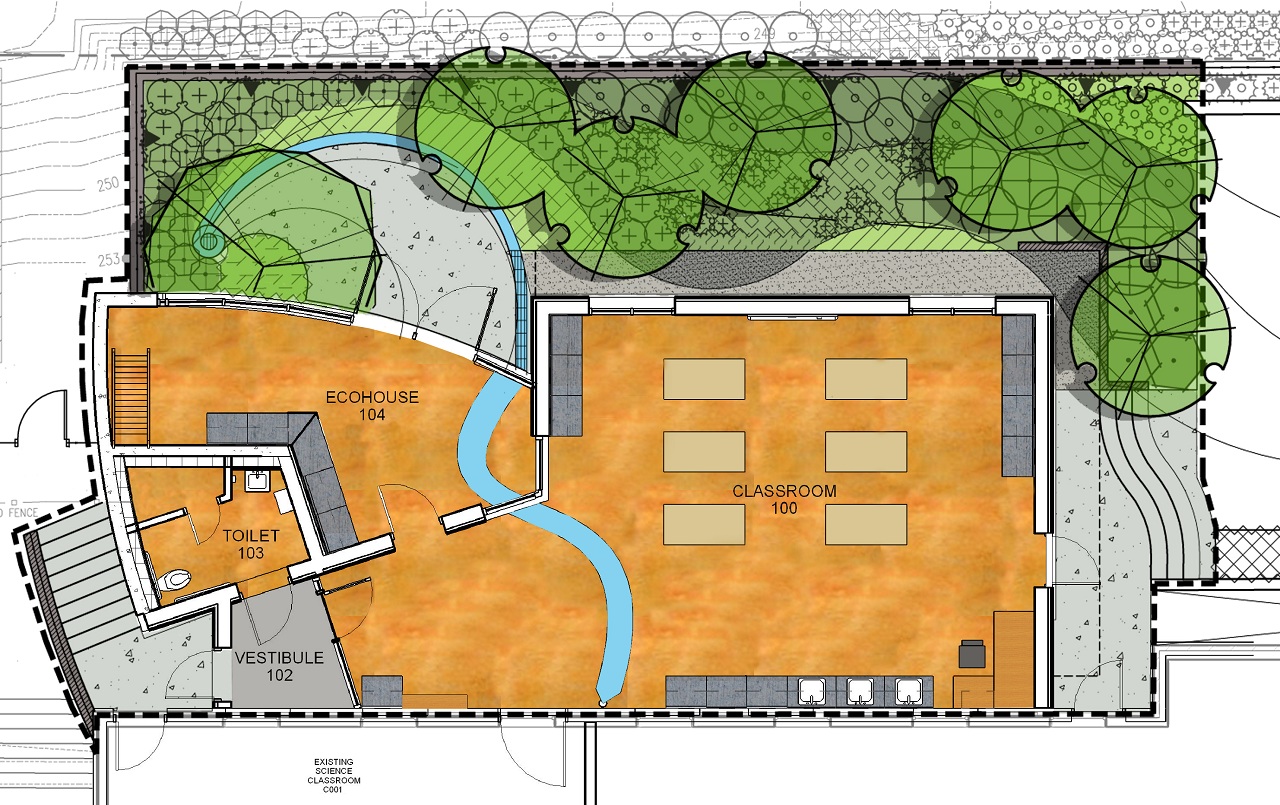

Just as the building is not permitted to pull a net positive amount of energy from the city’s electric grid, it is not permitted to use city water or discharge wastewater into the storm system, so rainwater is harvested and stored in a cistern. UV and carbon filters have been installed to make the water potable. Currently, however, the building is hooked up to the city water supply to meet its potable water needs because of local code requirements; governing bodies have been slow to allow commercial properties to manage their own water supply and treatment. “But health departments are definitely moving in that direction,” says Smedley. “They may require some regular testing and monitoring as we move to on-site treatment systems.”

"At the beginning of the design process, we asked the students what they wanted to see in the new building. They had a lot of creative ideas, and one of them was to have a river inside the building." Stacy Smedley, KMD Architects

To handle wastewater, a green roof will provide biofiltration of storm runoff, and greywater will be treated inside by a living wall of tropical plants. After it is purified, the water will be stored and reused. “We won’t have a blackwater issue,” says Smedley, “because we’ve installed a composting toilet.”

The classroom’s sustainable features will be leveraged as an educational resource for Bertschi School students, as well as for the general public, who will have access to tours of the facility once it is complete. “Monitoring equipment for water and PV power usage, in the form of digital readouts, is located around the classroom,” says Hellstern. “Teachers plan on using this as a teaching tool. For example, the math class will make charts and graphs using the data.” Also used in the curriculum will be plants from the school garden (which fulfils a requirement of the Living Building Challenge version 2.0 that the building support urban agriculture). “We included local vegetation -- the plants that native cultures used. And these plants will be used not just for food, but for things like art projects, where berries will be used for dyes and grasses will be used for weaving,” says Smedley.

Some of the classroom’s most remarkable features were conceptualized by the students themselves. “At the beginning of the design process, we asked the students what they wanted to see in the new building. They had a lot of creative ideas, and one of them was to have a river inside the building,” says Smedley. “So the concrete floor slab has a channel in it, and when it rains, water from the downspout flows through the space.” In this way, the kids can observe firsthand the building’s rainwater harvesting.

Smedley and Hellstern are appreciative of the fact that KMD was so willing to support the time and effort that they put into the Bertschi School project through the Restorative Design Collective. In the end, the profession as a whole will benefit from those efforts, as designers prepare to move forward and take sustainable design to the next level.

- Restorative_Design_Collective_Fact_Sheet.pdf (2559 Downloads)

Kristin Dispenza

Kristin graduated from The Ohio State University in 1988 with a B.S. in architecture and a minor in English literature. Afterward, she moved to Seattle, Washington, and began to work as a freelance design journalist, having regular assignments with Seattle’s Daily Journal of Commerce.

After returning to Ohio in 1995, her freelance activities expanded to include writing for trade publications and websites, as well as other forms of electronic media. In 2011, Kristin became the managing editor for Buildipedia.com.

Kristin has been a features writer for Buildipedia.com since January 2010. Some of her articles include: