Case Study: The Evolution of Miami Architecture

Picture Miami: a palm-dotted, pastel tableau with a bikini-required dress code. Then forget everything you think you know about Florida’s famous resort destination. Landing a commission in Miami has become a badge of honor among world-class architects. In particular, downtown Miami and Miami Beach host a growing collection of significant buildings connected by lively public spaces. The city’s success lies in its ability to reinvent itself while preserving itself. We explore the evolution of Miami's architecture through historical and economical lenses, the perspectives of influential practitioners, and the scopes of past and current projects.

Decoding Deco

“Miami is a young city with a long history,” observes William Cary, Assistant Director, Miami Beach Planning Department. “Every major economic event in America has changed the architecture of Miami Beach.” Although a few relics of vernacular architecture from the early 1900s remain, developer Carl Fisher receives credit for Miami’s love affair with Mediterranean Revival architecture. However, a 1926 hurricane wiped out much of his progress, and the 1929 stock market crash and the ensuing Great Depression cut Fisher’s gilded age short.

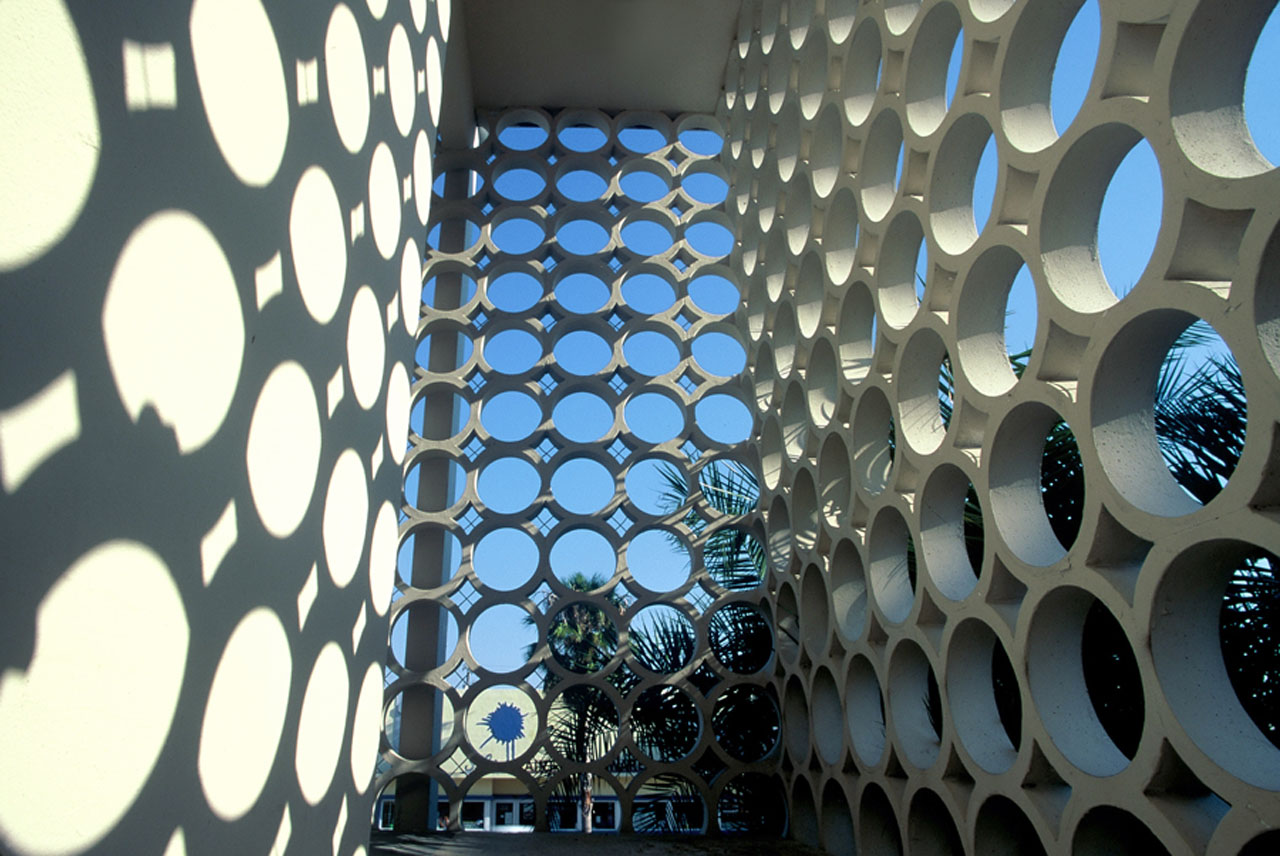

Soon enough, architects from New York and other northeastern cities, influenced by the Art Deco movement sweeping Europe, moved to Miami looking for work. These designers defined a new style for Miami, adapting Art Deco to suit the tropical climate. The look evolved with streamlined, rounded corners and nautical references like porthole windows. Throughout the Art Deco period, funds were invested in elaborate facades and lobbies. Expensive hardwoods and marbles were out of the question; instead architects articulated surfaces with local and high-impact materials like terrazzo, stucco, keystone, colored glass, and Vitrolite.

Miami quickly became known as a man-made paradise, and tourists arrived by the trainload. “The city streets, like Collins Avenue and Ocean Drive, became like stage sets and tourists became the actors on the stage -- that created the whole pedestrian ambiance, a wonderful collection of highly spirited, not deadly serious architecture,” Cary explains. Then they began to descend on Miami by car, and designers responded with circular drives and porte cochères. The defining Postwar Modern architecture of 1950s Miami – pioneered by Morris Lapidus, the architect of several Miami icons including the Fontainebleau and Eden Roc Hotels – has recently been rebranded as MiMo (pronounced my-moe, short for “Miami Modern”).

Push for Preservation

Miami’s economy collapsed again when air travel enabled tourists to jet to more distant destinations. In their absence, developers snatched up cheap waterfront real estate, and projects like public housing units positioned parallel to the beach were built without much regard for the historic fabric. However, tastes eventually shifted and people again found value in the Art Deco District, and in 1979 it was listed on the National Historic Register.

Ironically, it was the popularity of the 1980s television show "Miami Vice" that spurred international interest in revitalizing the struggling, crime-ridden city. Miami, specifically South Beach, served less as a backdrop and more as a character on the show. The opening credits flashed a sleek, mirrored tower with pastel accents: the Atlantis Condominium tower on Brickell Avenue was designed by the firm Arquitectonica, an edgy, experimental studio founded in 1977 in Miami. The firm became known for their abstract designs in bold colors and graphics – thoroughly modern buildings with a little Latin influence. Arquitectonica has continually played a role in shaping the city.

As Miami’s character evolved through the 1980s and 1990s, the planning board pushed to designate several more historical districts, which today number 11. Cary makes it clear, however, that Miami is not a museum full of artifacts, but rather a city that encourages innovation while demanding a high level of civic engagement. Designers are required to incorporate features such as glass storefronts and interactive indoor/outdoor spaces and make significant investments in landscaping design. Well known firms including David Chipperfield Architects, TEN Arquitectos, Herzog & de Meuron, and Gehry Partners have contributed to shaping the new landscape of Miami.

Reclaiming Public Spaces

Miami’s greatest asset, undeniably, is its beachfront. The city is one of the first successful examples of a pedestrian environment connected to a beach. Historically, thoroughfares like Lincoln Road, Espanola Way, Ocean Drive, and Collins Avenue attracted droves of tourists and locals alike. “That is what we built upon, the ongoing success of learning from the past and adopting strategies that proved to work, but using a whole new design vocabulary,” explains Cary.

Several recent projects illustrate the city’s commitment to reclaiming public space. Enlightened developer Robert Wennett selected Herzog & de Meuron to design a new “civic” parking garage at 1111 Lincoln Road, along with a public plaza envisioned by landscape architect Raymond Jungles. A native Midwesterner, Jungles maintains that “one of the things that attracted me to South Florida the most is the sense of freedom here, that you can move from indoors to outdoors.” He transformed this section of Lincoln Road into an outdoor living room, providing a backdrop for people to dine, play, people-watch and reconnect with nature. Jungles avoided the stereotypical non-native palms in favor of naturally occurring species including Live Oak and Cypress trees to create this “urban glade.”

Just down the street, the New World Symphony designed by Frank Gehry is surrounded by SoundScape, an urban park on the site of a former parking lot that was designed by Dutch firm West 8. Bringing the "green" back into the city was also a design priority here, as well as connecting pathways to move people through the site. Sculptural pergolas reflect the signature, jumbled forms within Gehry’s lobby while providing shade and defining entry points; they also conceal equipment for a large projection "screen" on the side of the building that will activate the space at night.

Following a similar approach at the tip of Miami Beach, Hargreaves Associates recently renovated the vastly underused South Pointe Park. The design introduces topography on what was flat land, weaving paths that regenerate urban connections and provide the perfect platform from which to view passing cruise ships. Another project underway that will change the way pedestrians connect with the waterfront on the other side of the bay is the Port of Miami Tunnel, which will reduce vehicular congestion through downtown caused by cargo trucks headed for the Port on Dodge Island, ultimately paving the way for future developments.

Downtown as Cultural Destination

Downtown Miami is known for its sparkling skyline comprised of residential high-rises, but it is quickly becoming the cultural heart of the city. However, that acknowledgement has not always been positive. From the mid-90s until it was finally completed in 2006, the Adrienne Arsht Center for the Performing Arts, designed by César Pelli, made headlines less for its design than for the long and arduous struggle over its budget.

The redevelopment of Museum Park, a 29-acre stretch along the bayfront also known as Bicentennial Park, is altering those public perceptions and promoting the awareness of downtown as a cultural destination. Terence Riley, founding parter of Keenen Riley Architects and the former director of the Miami Art Museum, played a lead role in the architect selection and design processes for the new building, which will serve as an anchor for the park. Herzog & de Meuron were awarded the project, and they created a building that responds to the tropical climate. A protective canopy conceals floating volumes and hanging gardens, integrating the structure with the surrounding park. “Unlike some architects who are known for a signature style, which often gets deployed anywhere on the globe without a lot of accommodation for the local culture, Herzog & de Meuron have made a really successful career out of doing precisely that – they have achieved an amazing cultural synthesis,” Riley believes. The Miami Art Museum is under construction and is anticipated to open in 2013. On an adjacent site, Grimshaw Architects have designed a new home for the Miami Science Museum, which will soon break ground. Like Herzog & de Meuron’s design, it incorporates extensive balconies and outdoor spaces throughout multiple levels.

El Nuevo Miami

Due to the current economic crisis, developers, particularly foreigners, are once again buying up attractive waterfront properties. Just to the north of Museum Park, a Malaysian developer has purchased the land around the headquarters of the Miami Herald and plans to create a $3 billion resort. They have selected Arquitectonica to design the project, and, given the firm’s legacy in the city, they will probably avoid the same mistakes as those unfortunate 1970s interventions.

Miami’s emerging architectural language does not attempt to recreate the glitz and glamour of the bygone Art Deco or MiMo eras, nor does it fall prey to those played-out "Miami Vice" stereotypes. Although a range of international architects are building for the first time in the city, much of the local flavor derives from the traditions of Latin America. Carlos Prio-Touzet, along with partner Jacqueline Gonzalez Touzet – both native Cubans and longtime Miamians – founded Touzet Studio. “We had always looked back at the tropical architecture of Cuba, and there was some element we were intrigued by – there’s a profound cultural mix,” he explains. The work of Touzet Studio captures that subtle balance that is the essence of the new Miami; it achieves sculpture through attention to detail and materiality rather than relying on flashy forms.

The new Miami draws from its past and respects its natural environment, adapting and reimagining proven tropical building methods. The resulting structures and landscapes are modern in every sense of the word, uniquely suited to time and place. Miami is surely a sophisticated city, but refreshingly it’s a city that doesn’t take itself too seriously.

A special thanks to Robin Hill for some of the great photography of the architecture of Miami featured in this article. See more of his work at www.robinhill.net.

Murrye Bernard

Murrye is a freelance writer based in New York City. She holds a Bachelor's degree in Architecture from the University of Arkansas and is a LEED-accredited professional. Her work has been published in Architectural Record, Eco-Structure, and Architectural Lighting, among others. She also serves as a contributing editor for the American Institute of Architects' New York Chapter publication, eOculus.

Website: www.murrye.com