The Controversy Surrounding Hydraulic Fracturing

Video

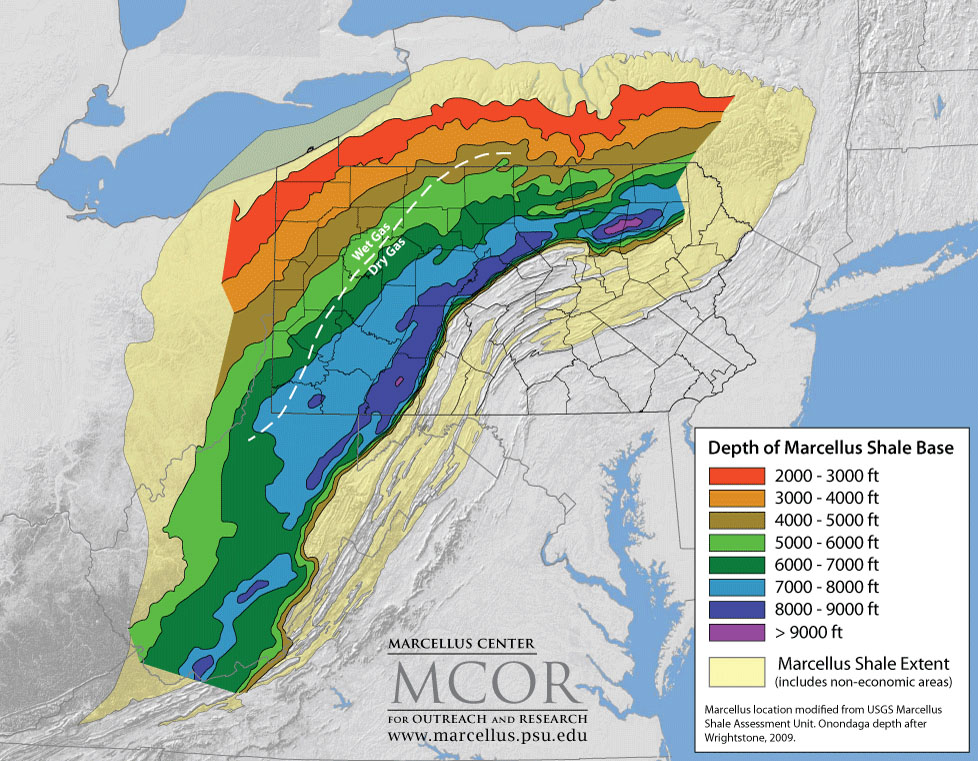

The Marcellus Shale, a subterranean rock formation that extends to 10 eastern and Appalachian states as well as Canada, may well become the proving ground for hydraulic fracturing, an increasingly controversial method of drilling for natural gas, with Pennsylvania currently the flashpoint of this controversy.

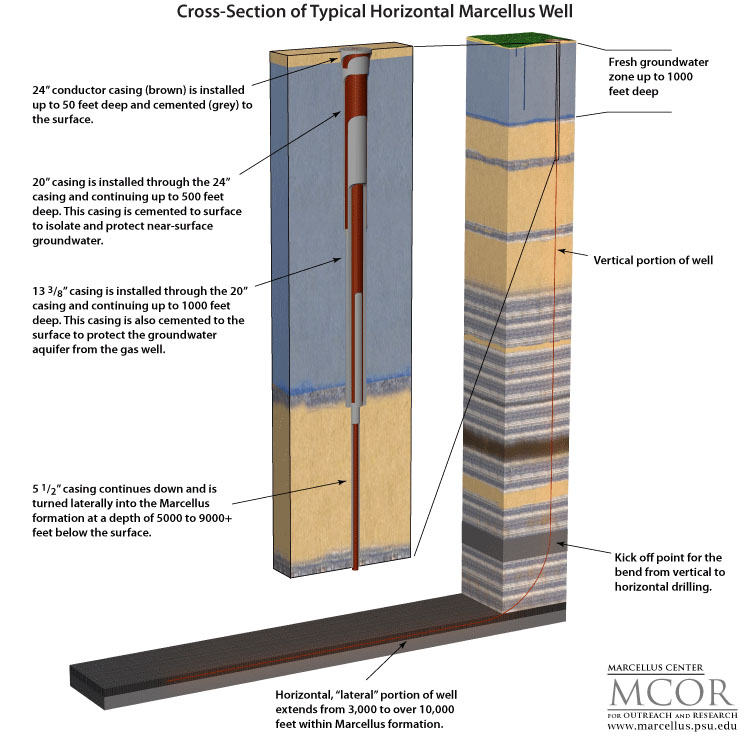

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, uses a pressurized mixture of several million gallons of water, chemicals, and sand to fracture the rock, releasing the natural gas present in the sedimentary shale play and allowing it to be piped to the surface. Energy companies have employed hydraulic fracturing to release natural gas in similar shale formations, notably the Barnett Shale in Texas and the Haynesville Shale in Texas and Louisiana, for years. According to Halliburton, which pioneered the use of hydraulic fracturing to stimulate the flow of natural gas in 1947 in Kansas, “Over the past six decades, hydraulic fracturing has helped deliver more than 600 trillion cubic feet of natural gas to American consumers, the product of more than 1.1 million separate and successful fracturing applications during that time.”

The Hydraulic Fracturing Controversy

Although originally hailed by the natural gas industry and the green movement alike as a safe, clean source of domestic fuel, hydraulic fracturing has come under growing scrutiny. Proponents of hydraulic fracturing point to its ability to end our dependence on foreign oil, to create jobs, and to lead to a new export industry and technology, originating in North America. Generally, energy companies and natural gas concerns maintain that this technology has a proven track record of safety, stating that hydraulic fracturing poses little threat to the quality of the groundwater and, ergo, the drinking water.

For example, Lee Fuller, executive director of the lobbying group Energy in Depth, posited that regulation and oversight on the state level would suffice, in his address to the National Press Club in October, 2007: “There aren’t instances of problems with hydraulic fracturing creating problems in groundwater. They haven’t occurred. It’s true in Pennsylvania. It’s true across the country. It’s a remarkable success story for the regulation of this technology. It’s not done by the federal government. It’s done by the states. So why do we have an issue here?”

At least two documentaries, Haynesville (2009) and Gasland (2010), have tried to answer that question, exploring the ways in which hydraulic fracturing changes the lives of those who live in the shadows of the drilling operations. Of these two, Gasland, which concerns the Marcellus Shale in Pennsylvania, has addressed the controversy in a more head-on manner. The image of a local resident igniting the flow of water from his kitchen tap serves well as an answer to the question posed so confidently by Fuller three years previously.

The controversy surrounding hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, has erupted in past weeks. In-depth reports have focused on the dangers fracking may pose to public health and wellness and the damage fracking may do to the environment. Without overarching federal regulation, each state that has natural gas resources must reach its own policy on a responsible method of gaining economically from the extraction of this resource via hydraulic fracturing. For instance, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo lifted his state’s ban on fracking in July 2011; his administration plans to regulate access to 85% of the shale play underlying the state. In another instance of how land-use policy is made without federal regulations in place, Bethany College, a private liberal arts school in West Virginia, signed a lease in the summer of 2011 with Chesapeake Energy to allow hydraulic fracturing on college-owned property.

Private business has responded to the boom of hydraulic fracturing, as well. An example of this response can be seen in LJ Stein & Company, which advises oil and natural gas companies on risk management and specializes in the Marcellus Shale area. Currently, LJ Stein & Company serves 200 businesses engaged in the extraction of natural gas in Pennsylvania, New York, West Virginia, Ohio, and Illinois.

Federal Regulations

In 2005, as part of the Energy Policy Act, Congress exempted hydraulic fracturing from compliance with the Safe Drinking Water Act by what is commonly (and unflatteringly) known as the Halliburton Loophole (due to the fact that then-Vice President Dick Cheney served as CEO of Halliburton from 1995 to 2000). Because of this exemption, hydraulic fracturing concerns do not have to make public the specific mixture of chemicals used when they drill for natural gas. Nor does the Environmental Protection Agency have the authority to investigate or regulate hydraulic fracturing operations.

President Obama’s administration has also confronted the question of whether, and how, to impose federal regulation on this industry and its technology. U.S. Senator James Inhofe (R-Oklahoma), ranking member of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, mounted a staunch defense on the Senate floor of the status quo (i.e., individual states regulating fracking) in July of 2009: “We must not impose new burdens on our exploration and production. Instead, we must open up supplies and use our domestic resources in new and innovative ways to create jobs and a new energy economy.”

However, in May 2011, Pres. Obama mandated the formation of a Natural Gas Subcommittee on the Safety of Shale Gas Development under the direction of U.S. Energy Secretary Steven Chu; members of the Natural Gas Subcommittee include the Secretary of Energy Advisory Board and representatives from the natural gas industry, states, and environmental experts. As well, the Departments of Energy and Interior and the EPA support the Natural Gas Advisory Board. The formation of the Natural Gas Subcommittee falls under Pres. Obama’s “Blueprint for a Secure Energy Future,” the stated mission of which is “to reduce America’s oil dependence, save consumers money, and make our country the leader in clean energy industries.”

To these ends, on July 13, 2011, the Natural Gas Subcommittee held a public meeting that streamed live at shalegas.energy.gov (the meeting agenda can be viewed on the website).

Secretary Chu sent a memo in May 2011 clearly delineating the scope of the Natural Gas Subcommittee’s work, which is to make recommendations for the following topics:

- well design, siting, construction, and completion;

- controls for field scale development;

- operational approaches related to drilling and hydraulic fracturing;

- risk management approaches;

- well sealing and closure;

- surface operations;

- wastewater reusal and disposal, water quality impacts, and stormwater runoff;

- protocols for transparent public disclosure of hydraulic fracturing chemicals and other information of interest to local communities;

- optimum environmentally sound composition of hydraulic fracturing chemicals, reduced water consumption, reduced waste generation, and lower greenhouse gas emissions;

- energy management and response systems;

- metrics for performance assessment; and

- mechanisms to assess performance relating to safety, public health, and the environment.

Natural Gas Subcommittee member Dr. Stephen A. Holditch, of Texas A&M University, says that the committee will publish its recommendations by August 19, 2011, and declined further comment before then.

Jennifer Randle

Jennifer has worked as an editor for various publications, including scientific journals, newspapers, and magazines. She graduated from Ohio University with a B.S. in journalism and is an experienced reporter as well. As the editor-at-large for Buildipedia, Jennifer enjoys knowing that readers can expect thoughtful and relevant content, publishing weekly in a timely and consistent manner.