The Erickson Building

Video

A new luxury residential tower in Vancouver provides a twist on the typology

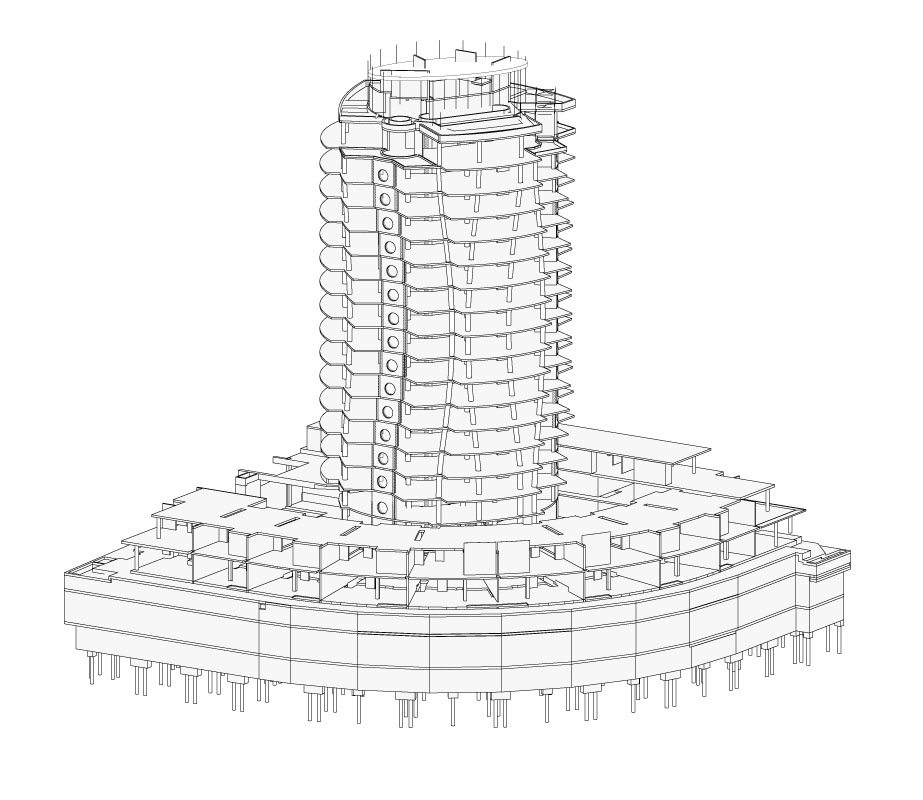

It’s not hard to imagine why developers flock to the waterfront of Vancouver, British Columbia. Concord Pacific Group has built many high-rise glass and concrete residential towers there, but the Erickson Building – a new 17-story, 61-unit development – stands out among their portfolio. Designed in the style of legendary Canadian architect Arthur Erickson, known for his modernist concrete structures, the Erickson’s twisting form rotates counterclockwise and then shifts clockwise, evoking the motion of the water below. Between concrete columns, expanses of glass capture panoramic views of downtown Vancouver, False Creek, the Strait of Georgia, and the Pacific Ocean beyond.

Doing the wave

Cast-in-place concrete was the obvious choice for the Erickson’s structure: it is highly customizable and sculptural, allows for a quick construction schedule, and is relatively inexpensive due to the availability of experienced local labor, explains Micheál O'Keeffe, a Structural Engineer and Principal with Glotman Simpson Consulting Engineers. Customization is key when every floor plate in the building is different. “Aside from the building waving along each of its four faces, the columns also perform a ‘wave:’ two follow the angle of the building, while two angle in the opposite direction,” explains O’Keeffe; “literally every floor has a different column layout, as these columns are shifting as the floor plates are shifting.”

Interior concrete columns must, of course, align vertically, but the perimeters of floors shift relative to their locations. Because the engineers and architects used Revit to define the tower’s spiraling form, they were constantly generating perspectival views from within to determine the optimal placement of columns without compromising views. With spans between columns constantly shifting, the engineers’ role was a balancing act. “We initially suggested going with post-tensioned members to the developer, but they didn’t want to use them,” recalls O’Keeffe, “so we had to make everything work with just mild reinforcing.” To maintain seismic stability, the engineers avoided transferring additional loads into the building’s core, its main structural support, which could cause it to lean dangerously in the event of an earthquake.

Balancing balconies and straddling parking spots

The Erickson’s private, cantilevered balconies are no doubt a selling point, but engineers had to carefully design the structure to accommodate their weight, including heavy planters. They knew it was inevitable that the balconies would deflect, so they counteracted those forces by cambering the concrete beneath. To keep the look clean, they designed a soffit to conceal the curve from below. At the same time, they had to minimize this deflection along the window line, which was infilled with NanaWall systems and would not tolerate subtle shifts.

Beneath the building, the engineers faced waterproofing issues and challenges in coordinating structural spans with the dimensions of parking spaces. The water table on the site rises to the elevation of finished grade, so the basement walls and structural members had to be designed to withstand hydrostatic pressure. To that end, the engineers specified Krystol Internal Membrane (KIM) by Kryton, a chemical admixture in the concrete mix. This process proved more successful than traditional waterproofing membranes, which the developer had used in similar developments nearby, but which had sprung leaks.

The developer asked the designers and engineers to create three levels of below-grade parking including private, gated garage areas for some tenants. These gated areas resulted in an odd spacing for the parking, and the structural bays did not stack well. The engineers struggled with transferring loads from the unusually-shaped building down to its pile-supported foundation but, after some pushing and pulling, were successful in accommodating all necessary parking spaces.

As O’Keeffe says, “There aren’t two matching floors in this whole building.” Despite the obvious challenges, however, the engineers ensured that this swirling building will remain stable and grounded and also managed to make concrete, a heavy and utilitarian material, look light, luxurious, and effortless.

Murrye Bernard

Murrye is a freelance writer based in New York City. She holds a Bachelor's degree in Architecture from the University of Arkansas and is a LEED-accredited professional. Her work has been published in Architectural Record, Eco-Structure, and Architectural Lighting, among others. She also serves as a contributing editor for the American Institute of Architects' New York Chapter publication, eOculus.

Website: www.murrye.com