2011 Solar Decathlon: Living Light in Tennessee

Video

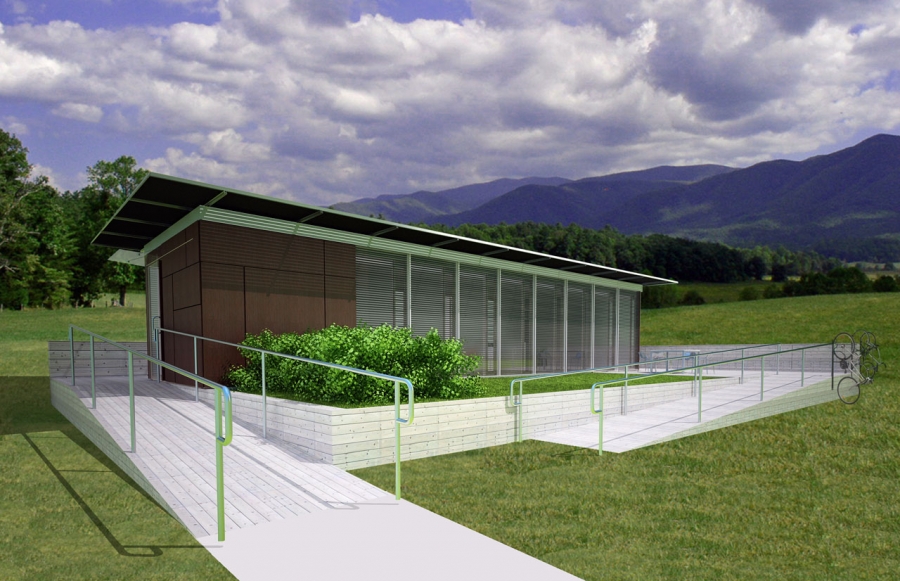

"Lightness" has several meanings, and the University of Tennessee’s 2011 Solar Decathlon entry, Living Light, exhibits them all. The design celebrates natural light, views, and ventilation, all within a compact footprint. The target audience for the home is young professionals working in the design or technology industries in Nashville. In other words, they appreciate all things high-tech but want a retreat at the end of the day. Living Light provides occupants with visual relief from the techni-cluttered world; energy-saving technologies are seamlessly integrated into the design.

Team members analyzed research on sustainable building materials and systems gained from the UT Zero Prototype, a collaboration between the school’s architecture, engineering, landscaping, and interiors departments. They applied this knowledge to the design of Living Light and also drew inspiration from the vernacular housing types of their ancestors, particularly the cantilever barns of southern Appalachia. Like these barns, the home’s design emphasizes horizontality, and its loft-like interior is organized around two dense cores pushed toward the perimeter; one houses the kitchen and laundry, and the other contains the bathroom, a Murphy bed, and desk. The cores are clad with a wood veneer that serves as a rain screen on the exterior.

The largest portions of the home’s north and south facades, however, are comprised of a dynamic double-glazed system that the team calls a "smart facade." “We challenged ourselves to allow as much light in without compromising the thermal envelope,” explains Steven Coley, Project Engineer. The glazed facades create the illusion that the home’s 750 sq. ft. interior – smaller than most Solar Decathlon entries, which are capped at 1,000 sq. ft. – feels much larger than it actually is.

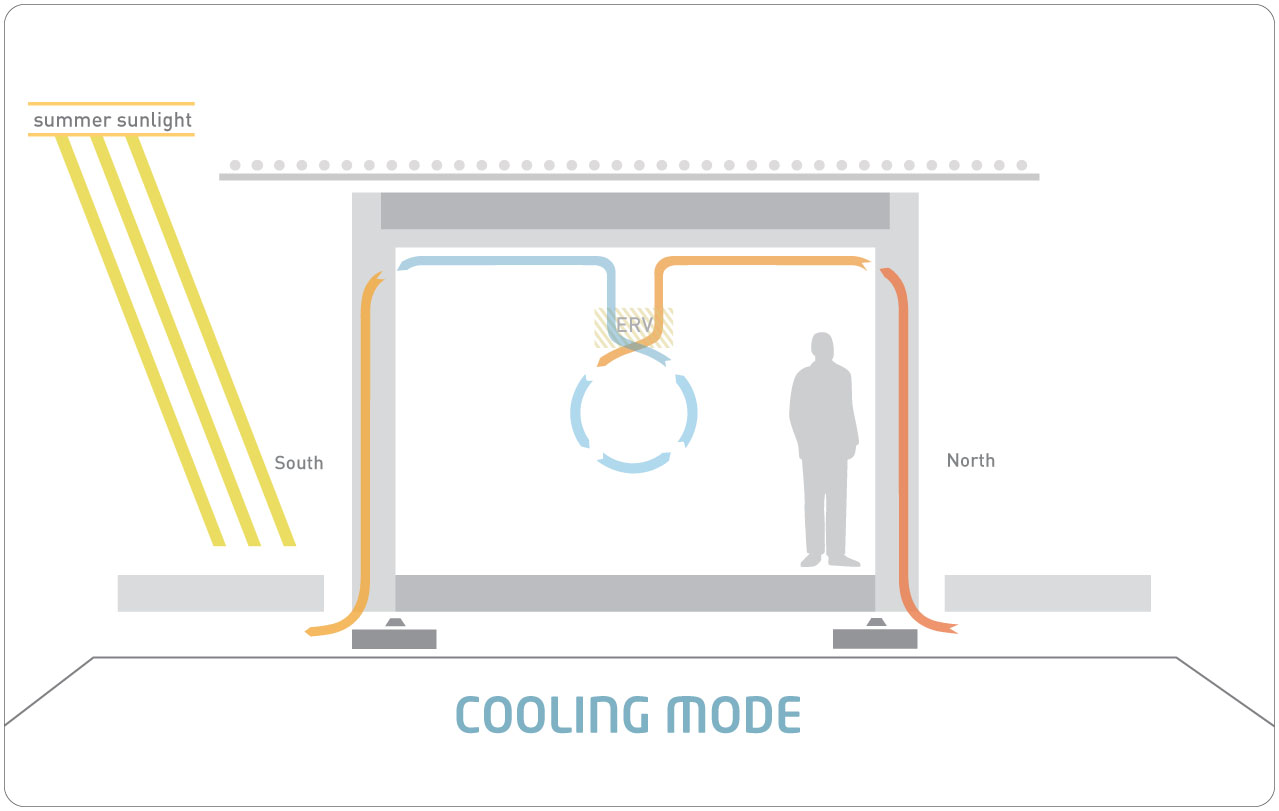

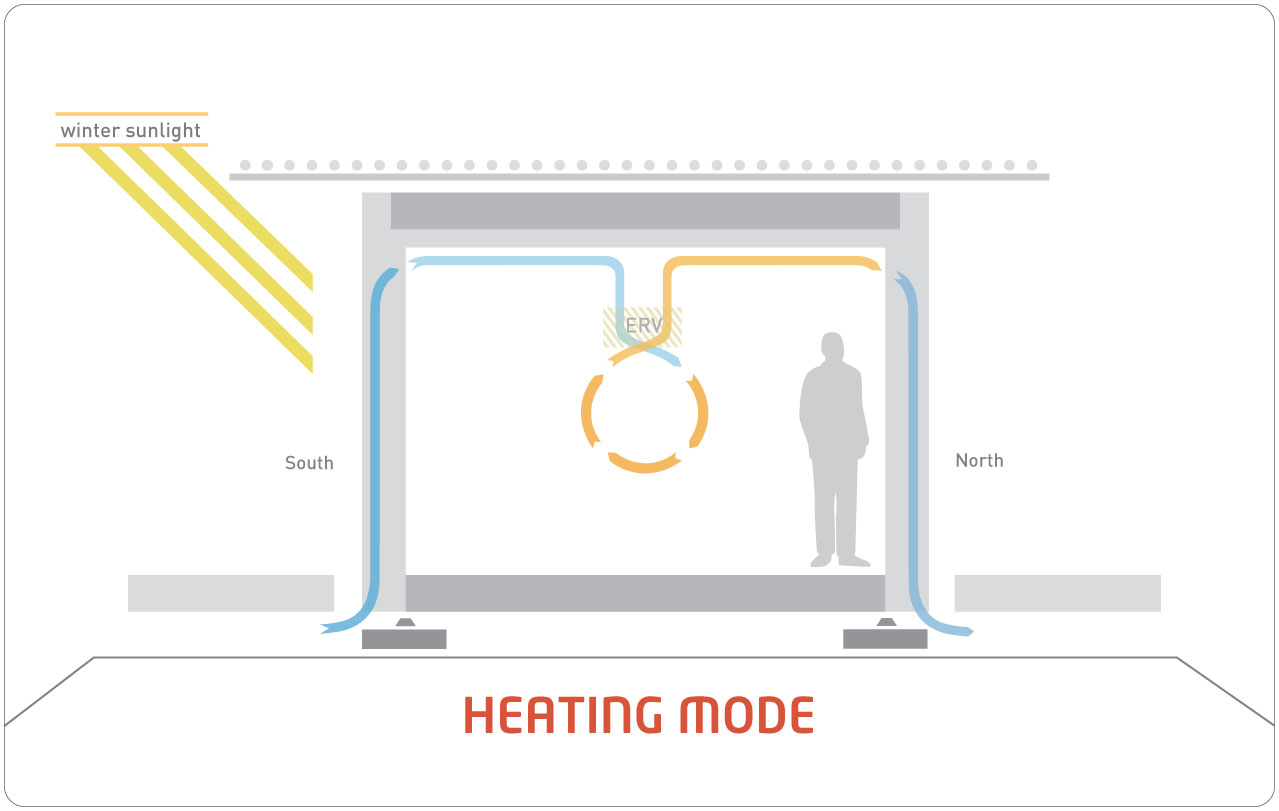

The facade system is comprised of several layers: a single pane of R-1 glass encloses an unconditioned air space that contains motorized horizontal blinds. Lining the interior is triple-pane R-11 glass in wood-veneered aluminum frames. On the north side this inner layer is translucent, but on the south side it is completely transparent in order to maximize daylight and views. Some of the facade’s glass panels are operable, allowing for natural ventilation. The unconditioned air cavity provides heat for the home in the winter via an energy recovery ventilator. In the summer, a fan exhausts this excess heat. This adaptable facade performs similarly to a solid standard wall construction in terms of energy efficiency.

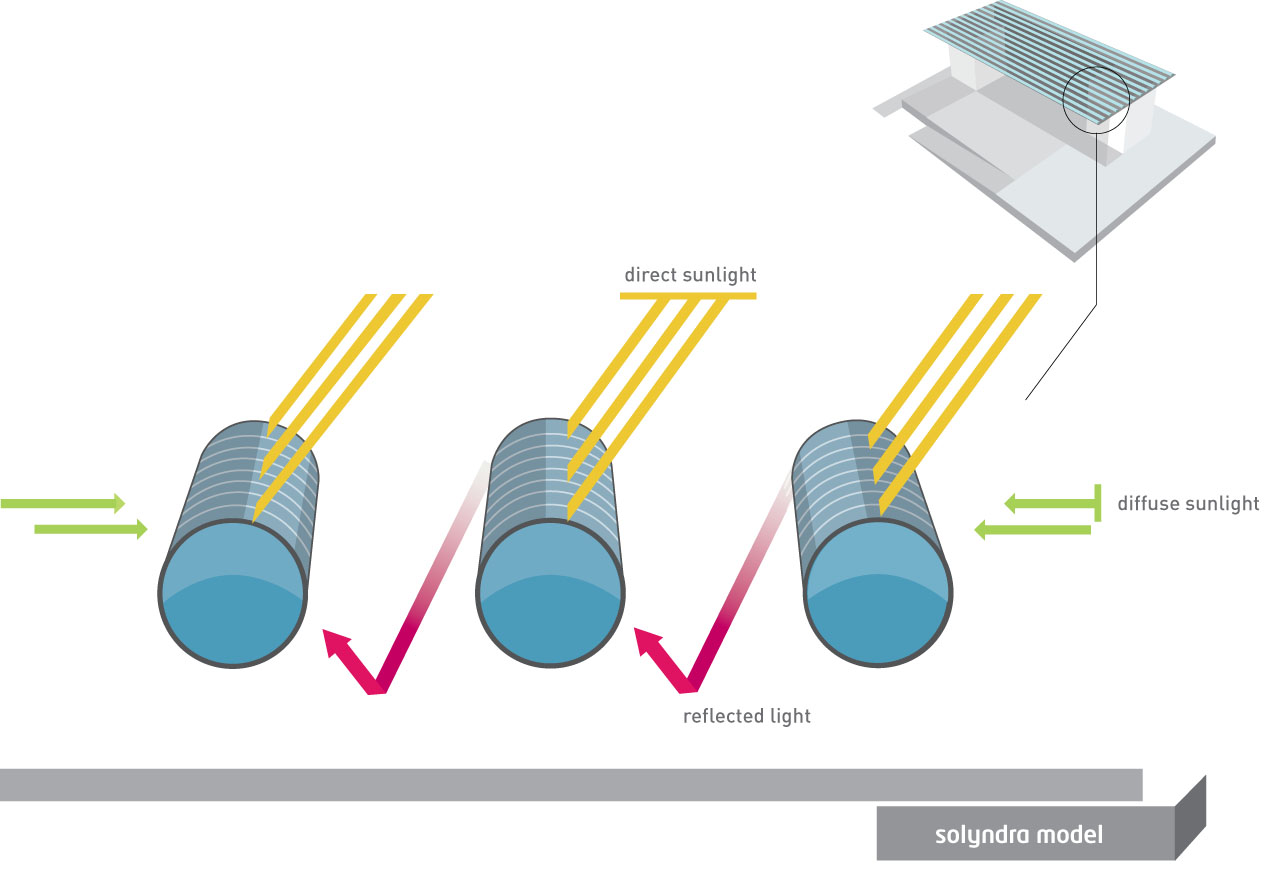

Although the team designed Living Light utilizing passive systems as much as possible, when it came to incorporating technology, they often went with off-the-shelf products. “We are using products differently than the manufacturer intended,” explains Amy Howard, an M. Arch graduate and Project Manager. For example, solar rooftop array panels also double as a shading structure. Even components of the double-glazed facade system are standard materials that can be purchased from a local home improvement store.

The home’s truly high-tech elements are concealed from view but allow occupants a great deal of customization. Lighting sensors adjust to create moods for different scenarios, including watching movies, entertaining guests, or even going into vacation mode. Additionally, strips of color-changing LEDs line the glazed facade and allow for a soft transition between night and day, and vice versa. The homeowner can monitor energy use with an iPad, allowing him or her to “be a more informed consumer,” according to Howard.

After Solar Decathlon 2011, Living Light will tour Tennessee before returning to the University of Tennessee campus to serve as a learning laboratory. However, the team envisions it as part of a larger development. Such a neighborhood would allow young professionals the loft lifestyle they desire along with the benefits of owning their own land – the greatest of which is the chance to reconnect with the landscape.

Murrye Bernard

Murrye is a freelance writer based in New York City. She holds a Bachelor's degree in Architecture from the University of Arkansas and is a LEED-accredited professional. Her work has been published in Architectural Record, Eco-Structure, and Architectural Lighting, among others. She also serves as a contributing editor for the American Institute of Architects' New York Chapter publication, eOculus.

Website: www.murrye.com