The Impact of BIM on Construction Law

From green building to Building Information Modeling (BIM), new technologies are changing the construction game and changing it fast. What legal and contractual protections can be put in place as the workplace adopts these technologies?

There’s no question that, in the design and construction industries, Building Information Modeling (BIM) is what’s termed a “disruptive technology.” Since the 1980s, when PCs finally became affordable enough for architectural practices to begin to bring them to bear on design, computing power has become ubiquitous and increasingly influential on budgeting, programming, design, and construction.

As all good technological disruptions go, BIM found an uneven acceptability in the early stages of its adoption by the design and construction industries. Although architects readily adopted the 3D rendering power and visual manipulation capabilities of BIM, to a great degree the construction industry and building owners have still insisted on the production of paper documents, a time-honored and risk-adverse means for getting buildings built and in-hand records kept, insuring the existence of a “paper trail.” Of course, exceptions exist in both camps; small design firms and boutique offices often use BIM to the max, with the cooperation and support of their forward-thinking and resourceful compatriots on the construction side. Architectural firms seeking to meet their more sophisticated clients’ demand for technological savviness employ BIM as a way of profoundly improving constructability.

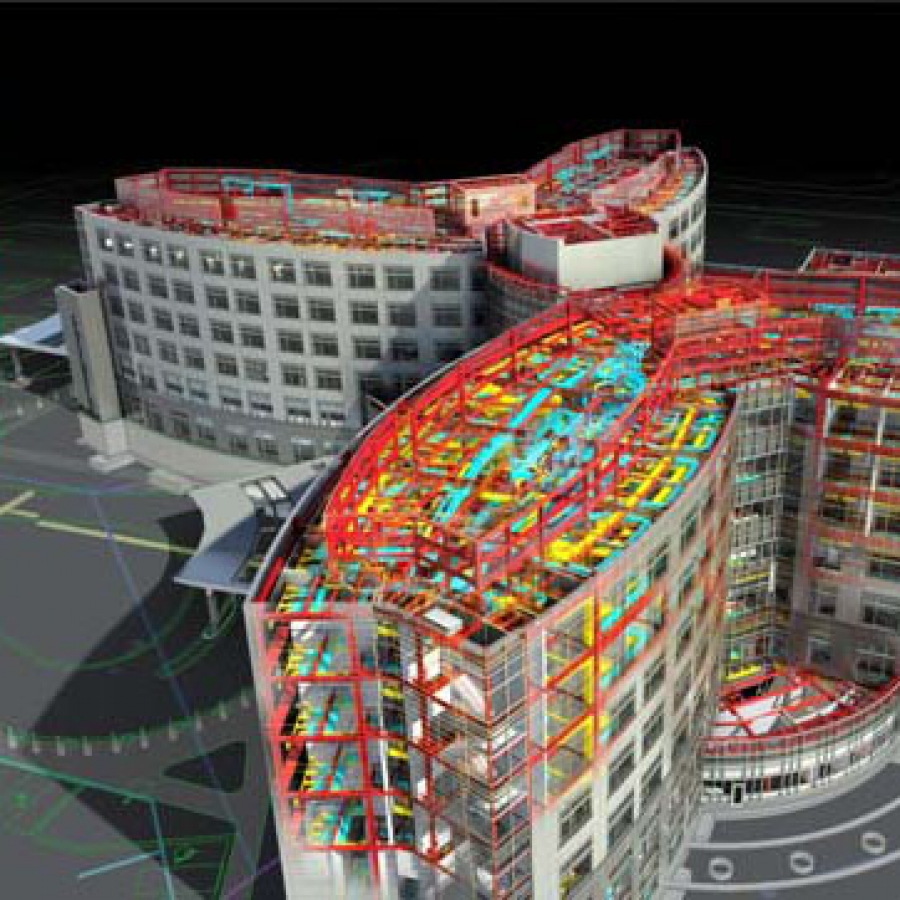

BIM is particularly useful in projects with little repetitive geometry, such as Daniel Libeskind’s first American building, the Frederic C. Hamilton expansion to the Denver Art Museum, which was constructed by Mortenson Construction in cooperation with Libeskind’s American office associate, Davis Partnership Architects. The Davis Partnership Architects / Mortenson Construction team went to extraordinary lengths to successfully produce 3D structural plans that provided the basis for fabricating the sophisticated and complicated steel structure of the building. Mortenson Construction, in an integrated project delivery (IPD) team setting, used the BIM models to design columns needed during construction to hold up the partially completed structure while supporting permanent structural members were placed and bolted together. Indeed, the Denver Art Museum highlighted the colorful BIM models in a popular exhibit about the building’s evolution as a work of art, including the obligatory 3D fly-through, fly-around video.

One of the primary factors in the success of the Denver Art Museum expansion was the overwhelming support and enthusiasm of a cosmopolitan, well-heeled client situated in a progressive, design-oriented city. A continuity of communication among the client, architects, contractors, and tradesmen provided the basis for a successful project that had special meaning given the complexity of the design and corresponding difficulties in constructing this geometrically elaborate museum. Unfortunately for the industry, such circumstances don’t always prevail, and trouble ensues.

The construction and design industries have been recently “disrupted” by the publicity surrounding the inevitably high-profile disputes in which detractors focus on BIM when assigning blame in a troubled project. During the construction of a life sciences building outlined in the May issue of Engineering News Record (the identity of the project was undisclosed), the building’s design process passed pre-design constructability muster. Architectural and engineering collision detection software was used to analyze its BIM models, but during construction it was discovered that, although there was room for a critical piece of mechanical equipment in the ceiling plenum, other building elements in the vicinity made it impossible to place it without a very costly dismantling and reconstruction process. Although the sequencing for equipment placement was known, it wasn’t successfully communicated to the contractor. Litigation was pursued to recover damages in an attempt to keep the owner and contractor financially whole. As outlined in the article, Randy Lewis, Vice President of Loss Prevention and Client Education at XL Insurance, said, “Everything fit in the model but not in reality, and it was a very costly claim to negotiate.” (XL Insurance provided the professional liability insurance to consultants in the project.)

Such incidents may cause clients, architects, and builders to huddle with their attorneys and insurance providers to make sure that they’re somewhat immune to the travails of this kind of litigation. However, significant proactive efforts have been made to ensure that fear of litigation doesn’t have to be a BIM adoption deal-breaker. The Lean Construction process can take advantage of many of the software-based communication, collaboration, supply chain, and project management tools now available, together with the adoption of any of the many forms of Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) to save significant time and money–benefits outweighing those gained by sticking to conventional design-bid-build construction project delivery. Of course, a project’s success using Lean Construction methods depends on the leadership of high-quality, win–win-oriented clients, who also often incentivize the team players as “insurance” for a project’s smooth delivery and successful outcome.

A primary contractual tool is being added to the design and construction industry tool belt in the form of the American Institute of Architects AIA E202-2008, Building Information Modeling Protocol Exhibit. This document charts the relationship and responsibilities of all parties to a design and construction project. The AIA E202-2008 document contractually outlines the levels of development, model elements, element authors, and protocols for coordination and conflict, model ownership, model requirements, and file format. It also provides an outline of model management, listing responsible parties and project phases, as well as a description of initial and ongoing responsibilities for the ownership and use of the BIM models.

According to attorney and construction industry adviser James Salmon, President and Founder of Collaborative Construction Resources, LLC, “Use of consensus agreements is a big step in the right direction. If you have a good enough incentive program, that may begin to give everyone traction, providing direction for everyone to row in the same direction.”

Green Building and Beyond

Perhaps confounding matters for the design and construction industries more recently, the institutionalization of green and high-performance building processes add complexity, with clients rightfully challenging their project teams to use energy-saving and environmentally responsible strategies to accomplish budgetary and corporate sustainability goals with their buildings, both new and remodeled. The U.S. Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) rating process has become a routine checklist for high-quality, high-profile projects industry-wide; software-based energy modeling demonstrates significant hoped-for savings via the lowered consumption of fossil fuel-based resources and the corresponding shrinking carbon footprint. Unfortunately, even with the building commissioning part of the LEED rating process, which is intended to ensure that a building’s energy system is operating correctly, many LEED-rated buildings are reportedly not operating at levels promised to owners by the design team. According to Salmon, “There is an entire generation of LEED buildings out there that aren’t delivering. Well meaning politicians fail to grasp how hard high-performance building is to accomplish.”

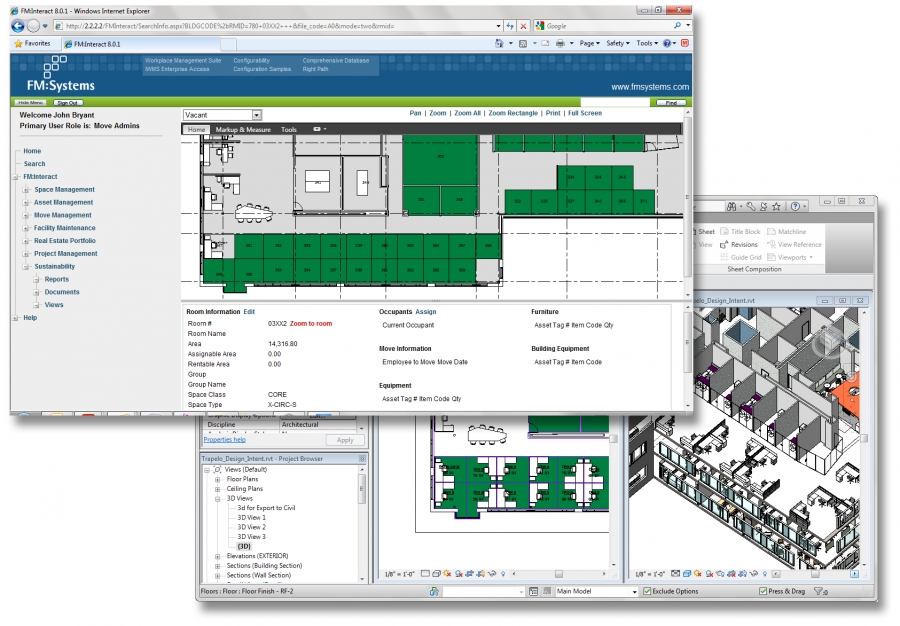

Critical building components can have an embedded, Web-addressable life beyond the limitations of the traditional three-ring-binder operations and management (O&M) manual. This technological advance will increase the use of the “smart” capabilities of those components to improve the well-being of our buildings’ occupants. Salmon continues, “We also need to look beyond the design and the specific building, we need to zoom out and say what kind of legal framework is there for BIM and integrated project delivery, from conception through decommissioning, gathering data, and handing it off to the next person, allowing them to leverage that data, and so on at each stage so that the information is embedded in the building’s operation. That can’t happen unless there are contractual mechanisms for requiring that as a deliverable. Right now we’re focused on what we draw. We need to bundle this critical data that can be handed off from one person to the next. An enormous amount of data can be captured. We need to but still haven’t gotten any comments or feedback that brings the subs and suppliers into the process. We need to reach into the supply chain to make this happen.”

Undoubtedly, the gradual adoption of cloud-based computing and subscription-based, continuously updated software delivery will usher in a disruptive but positive wave in the construction and design industries, where the availability of supercomputer resources and nearly unlimited storage capacity could bring a nearly universal adoption of Building Information Modeling (BIM). BIM can provide architects, contractors, owners and developers, and the honorable building trades with tools unequaled in the history of humankind’s ability to shape our environment, for better and for worse. These “disruptive technologies” create even more potential for us to design and construct successful, environmentally responsible high-performance buildings.

Morey Bean, AIA, LEED AP

Colorado's 1999 Architect of the Year and Vice Chair of the Boulder Chapter of the Urban Land Institute, Morey’s experience includes the successful development of the Colorado Architecture Partnership, an architecture firm dedicated to sustainability and green building. Morey was appointed by the Chief Architect of the GSA to the National Register of Peer Professionals. He serves as a ULI Service Advisory Panelist and was a charter member of the Colorado Chapter of the USGBC and past president of the Colorado South Chapter of the AIA. He is a construction litigation services expert witness, land development analyst and sustainability strategies consultant.

The author was honored by the Colorado Component of the American Institute of Architects as their Architect of the Year in 1999 and is on the Roster of Neutrals for the American Arbitration Association (AAA), providing dispute settlement for the design and construction industry.

Website: www.cyberarchitects.com