2010 Olympics Begin: Vancouver Convention Centre

In 1978, municipal, provincial, and federal Canadian governments began working together to plan the development of a convention center – complete with cruise line and hotel amenities -- on a waterfront property in Vancouver that had been used earlier in the century as a railway pier.

Vancouver Convention Centre | Credit: LMN Architects

Vancouver Convention Centre | Credit: LMN Architects

By 1986, when the World's Fair was held in that city, it was able to boast one of the most noteworthy host facilities of all time: Canada Pavilion, with its distinctive white sail roof, and the adjoining Canada Place convention center.

Now more than twenty years have passed, and it is again time for Vancouver to host a world-class event. The 2010 Winter Olympic Games begin February 12, and again Vancouver has a stunning new facility to match the prestige of the occasion. In April 2009, the 1.2 million sq. ft. Convention Centre West opened. Built upon a former brownfield that was the last undeveloped piece of property on the harbor front, it functions as an expansion of Canada Place. The facility covers 14 acres of land and eight acres of water, and is connected to Canada Place via landside walkways. It was designed by Seattle-based LMN Architects, in collaboration with Musson Cattell Mackey Partnership and DA Architects & Planners, both of Vancouver.

The New Convention Center Takes its Place in the Vancouver Cityscape

The Convention Centre West will house the more than 7000 VANOC accredited media representatives who will be covering the 2010 Olympics. But this $883,200,000 CAN ($837,400,026 US) building (figure includes renovations to the existing Canada Place facility and associated infrastructure improvements) is not a specialized structure designed for one-time use. According to Jacques Beaudreault, a Partner at Musson Cattell Mackey Partnership, “The project was started in Feb. 2003, and was originally intended to be a new convention center -- so the start of the process worked out nicely with the beginning of planning for the Olympics.”

The Convention Centre West will house the more than 7000 VANOC accredited media representatives who will be covering the 2010 Olympics. But this $883,200,000 CAN ($837,400,026 US) building (figure includes renovations to the existing Canada Place facility and associated infrastructure improvements) is not a specialized structure designed for one-time use. According to Jacques Beaudreault, a Partner at Musson Cattell Mackey Partnership, “The project was started in Feb. 2003, and was originally intended to be a new convention center -- so the start of the process worked out nicely with the beginning of planning for the Olympics.”

Olympic Spotlight

Vancouver Gathers At Robson Sq

The Olympics: Vancouver Sets the Green Stage

A Remarkable Torch Starts the Olympics Opening Ceremony

Vancouver City Councilor Suzanne Anton on Eco-Density

With this larger goal of serving the community in mind, creating a strong connection between the building and the rest of Vancouver was a primary concern from the beginning. “The physical surroundings and the open spaces that constitute the public realm were the most obvious considerations, but when evaluating the site’s context, LMN tried to think more broadly than this,” says Mark Reddington of LMN Architects, Design Partner for the project, “We recognized the ecosystem, the infrastructure – roads, water, sewer – and the natural landscape.” As a third and equally important factor, LMN studied the building’s impact on civic life. Then, taking all of this into account, LMN looked for a point of intersection. Says Reddington, “Our process was to examine each of the possibilities in its own category, and then put it all together and look for overlap. We had to find a way to address all of these things in one way.”

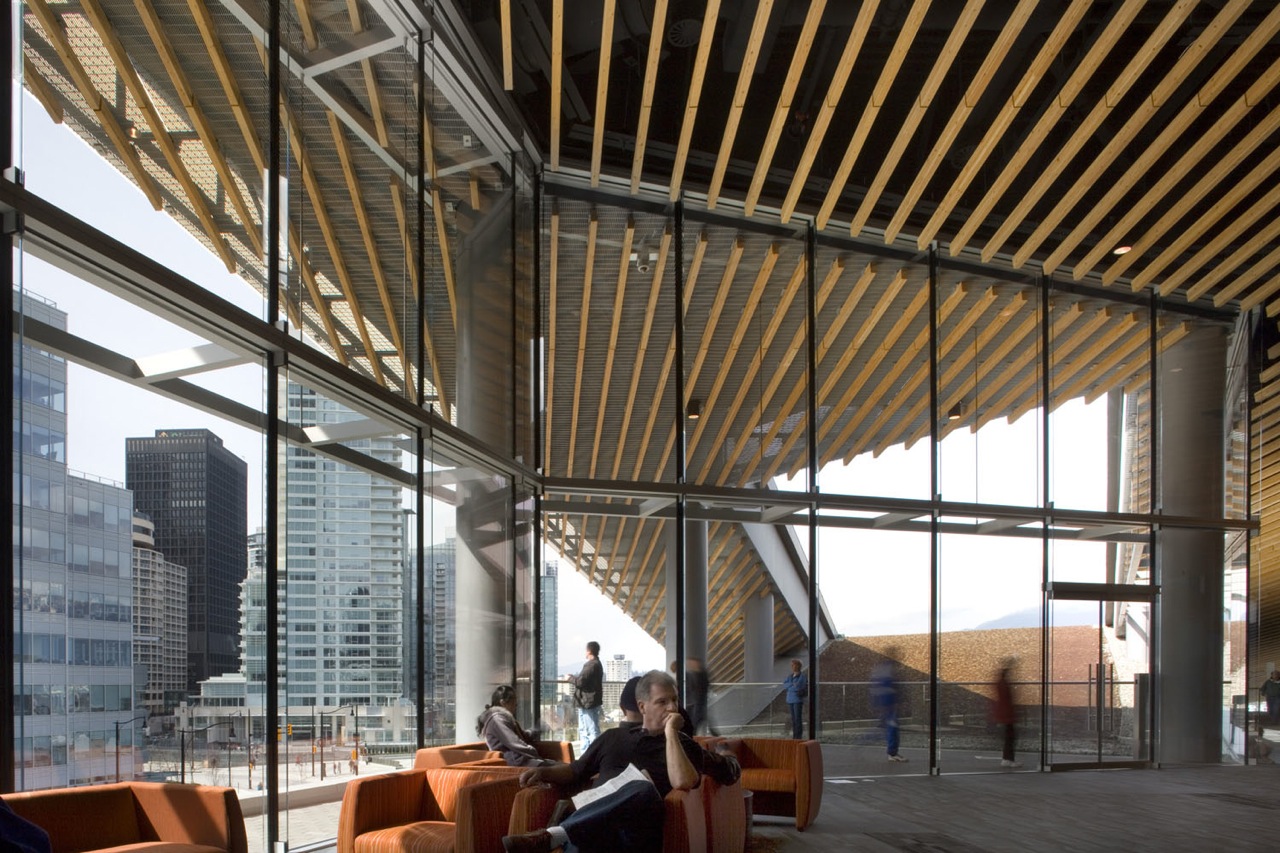

The designers’ solution was to create a built form that is integrated into both the landside environment and the landforms surrounding it. The Centre acts as an extension of the existing waterfront park, and establishes view corridors from the downtown core onward to nearby Stanley Park, the harbor, and the mountains beyond. From inside the building, views are framed of downtown Vancouver; the convention center’s green roof, in turn, enhances the view from the surrounding skyscrapers.

"Vancouver already believed in sustainability." Mark Reddington, LMN Architects

Not only is the form of the building exceptional, but its function as a center for civic life is as well. In addition to drawing out-of-town visitors, it is a popular venue for local events and provides day-to-day amenities and services. Reddington says, “What’s exciting is the widespread excitement that the building has generated. The community has adopted it. During a two day open house, 65,000 people came to see it.”

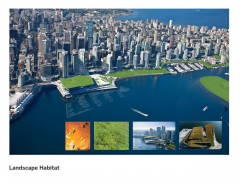

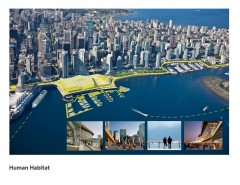

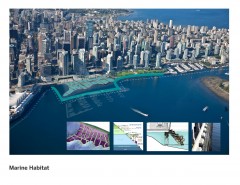

Vancouver, more than many places, has had to come up with inventive ways to serve its local community; since the city is on a peninsula, its growth is severely constrained… and, according to one source, the population of the downtown core more than quadrupled between 1981 and 2001. Fortunately, Vancouver was an early adopter of high density planning practices, and since the 1980’s its city council has assertively promoted a “Living First” strategy, changing zoning to allow for more residential development. Having such a large population living downtown places special demands upon every developed square foot of space, and every built form is called upon to serve multiple functions. The Convention Centre West lives up to these special demands. According to the architects, it triples the total square footage of the public realm on the waterfront. In fact, it is so multi-tasking that it has three distinct functional layers: landscape habitat, human habitat, and marine habitat.

Landscape Habitat

One of the most pressing concerns for a densely packed living environment is having enough green space. But Vancouver has also shown a history of progressive planning practices when it comes to setting aside green space and prioritizing ecological concerns, so the aspirations for the Convention Centre West, which achieved LEED Canada Platinum certification, didn’t change Vancouver’s overall direction. “Vancouver already believed in sustainability,” says Reddington.

The building owner, BC Pavilion Corporation (PavCo), a Crown Corporation of the Province of British Columbia, was the initiator of the high green standards, according to Beaudreault. “They set the policy and design principles. They were adamant that everything that was incorporated into the building made sense for that building, and for the long term objectives of the building,” as opposed to perfunctorily fulfilling LEED requirements.

One of the most spectacular green features of the building is its six acre living roof (the largest in North America). Since the building functions as an extension of the park system, acting as a link in the continuous waterfront ring of green spaces, this feature completely fits with the objective of the building. It is home to an impressive 400,000 indigenous plants as well as several hives of bees!

Human Habitat

The Building’s Form

The distinctive form of the convention center took shape in response to interior requirements as well as to outside influences. It accommodates a variety of programmatic functions, including one million sq. ft. of convention space (with exterior plazas and walkways, a ballroom, meeting rooms, and exhibition space), 90,000 sq.ft.of retail space, and parking, so “the geometry of the roof tried to do a couple of things,” says Reddington. For example, the “ballroom needed to be big and tall. Other interior spaces needed to be smaller in scale, with lower ceiling heights. The lobby needed to frame multiple views.” Ultimately, LMN arrived at a building shape that included sloping roof planes. “The shapes are an extension of the ground plane, reflecting the topography of the region, and they help the building blend into the waterfront. The existing habitat provided the parameters for the slopes.”

To provide continuity between its interior and exterior, the entire building perimeter is glazed. “To make this possible,” says Reddington, “lobbies and other public spaces occupy the outside of the building footprint; more private zones are located at the core of the building.” To avoid visual disruption, Beaudreault says, “For the curtainwall, instead of aluminum mullions, we used glass fins for structural support so that the views out to the water and to the mountains beyond would not be obstructed.” This transparent boundary helps tie in the 400,000 square feet of walkways, bike paths and open spaces that the center provides beyond the building envelope.

The Building’s Utility Systems

The project’s utility systems feature some cutting-edge sustainability elements. Potable water use has been reduced by 60 to 70 percent over typical convention centers by taking black water – the building’s own sewage water – and treating it sufficiently to make it usable for gray water applications (e.g., irrigation during the dry season, toilet flushing, etc.). In fact, over 80 percent of the building’s gray water needs are met in this way; a 10,000 gallon storage tank is constantly being replenished. The center also has a desalinization plant on site, which draws water from the harbor and processes it to meet additional non-potable water demands.

"What’s exciting is the widespread excitement that the building has generated. The community has adopted it. During a two day open house, 65,000 people came to see it." Mark Reddington, LMN Architects

According to Beaudreault, the building’s mechanical system actually surpassed initial expectations in terms of sustainability. (In fact, the original LEED goal for the overall building was Gold, and it ended up achieving Platinum, so one of the noteworthy aspects of this project was its ability to exceed expectations!) Says Beaudreault, “The original mechanical plan was to extend Canada Place's plant to heat and cool the new addition, but that didn't work out financially. So we designed a new mechanical system, using seawater cooling/heating through heat exchangers. We ended up with our own plant, and hadn’t originally planned for square footage for a mechanical plant, so that was a problem to solve. It threw us a curve ball.” The system used is similar to geothermal technology, except that a heat pump pipes water from the harbour, and it is the constant temperature of seawater that is used to heat and cool the building. In very cold weather, steam augments the heating system. Demand on the mechanical system is also reduced by the living roof, which acts as an insulator.

Natural ventilation and extensive daylighting not only contribute to the building’s sustainability goals, but also enhance the user experience. The generous amount of glazing which admits natural light into the space required particular attention in its detailing, especially to ensure its durability.

CaGBC (Canadian Green Building Council), which was not in place when the building was started, but was introduced in 2004, awards a point for durability in the LEED Canada NC - 1.0 Materials and Resources category, and this influenced not only the selection of materials for the center, but also methods of installation. Says Beaudreault, “The building envelope consultants, Morrison Herschfield Limited, spent a lot of time on site overseeing how the curtainwall was being constructed to ensure it was done correctly. They were looking primarily to make sure there was no cold bridging or gaps in the insulation, and also spent an enormous amount of time detailing and reviewing shop drawings.”

For the category of Energy and Atmosphere, CaGBC awards 17 points, and 10 of these are for optimizing energy performance. The Convention Centre West earned all ten. Overall, it earned 52 points for its certification, out of a possible 70.

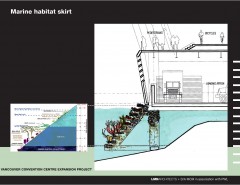

Marine Habitat

Ecological considerations weren’t limited to concerns above the water line. Along the waterfront, an artificial reef shelters salmon, crabs, starfish, seaweed, and other marine animals. The concrete ‘skirt’ steps down in five tiers from the underside of the public walkway into the harbor. Tides cause seawater to flush the area daily. The skirt was designed with input from marine biologists and other consultants to make it mimic a natural environment, and plans were put in place to restore the habitat of 200 ft of contiguous shoreline.

An Example of a Sustainable Future

It is fitting that the Convention Centre West should have a role to play in the 2010 Winter Olympics, because just as the Olympic games traditionally serve as a reminder of the collective goals of humanity, a beautiful structure that is built in a sustainable, forward-looking way can also serve as a reminder of our collective goals. And after its moment in the international spotlight has passed, this convention center will continue to exemplify the direction of the future by demonstrating that, even in the midst of a crowded city, a building can provide not just for the various needs of the human community, but for the needs of the ecological community as well.

Kristin Dispenza

Kristin graduated from The Ohio State University in 1988 with a B.S. in architecture and a minor in English literature. Afterward, she moved to Seattle, Washington, and began to work as a freelance design journalist, having regular assignments with Seattle’s Daily Journal of Commerce.

After returning to Ohio in 1995, her freelance activities expanded to include writing for trade publications and websites, as well as other forms of electronic media. In 2011, Kristin became the managing editor for Buildipedia.com.

Kristin has been a features writer for Buildipedia.com since January 2010. Some of her articles include: