A "library park" in a Colombian barrio serves functions beyond those of either a library or a park. State-funded programs operated through the institution provide an underprivileged community with educational and other services, making the Parque Biblioteca España a symbol of hope for the city of Medellín.

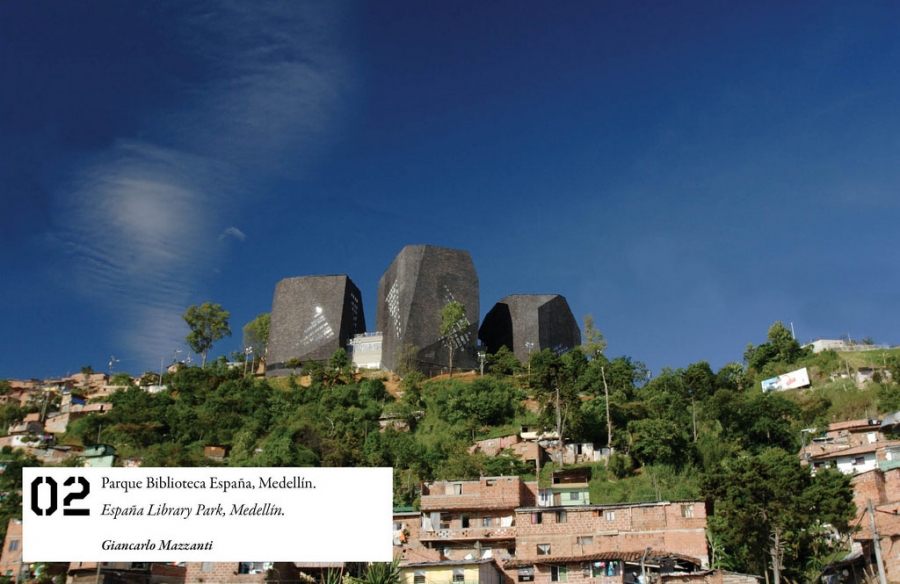

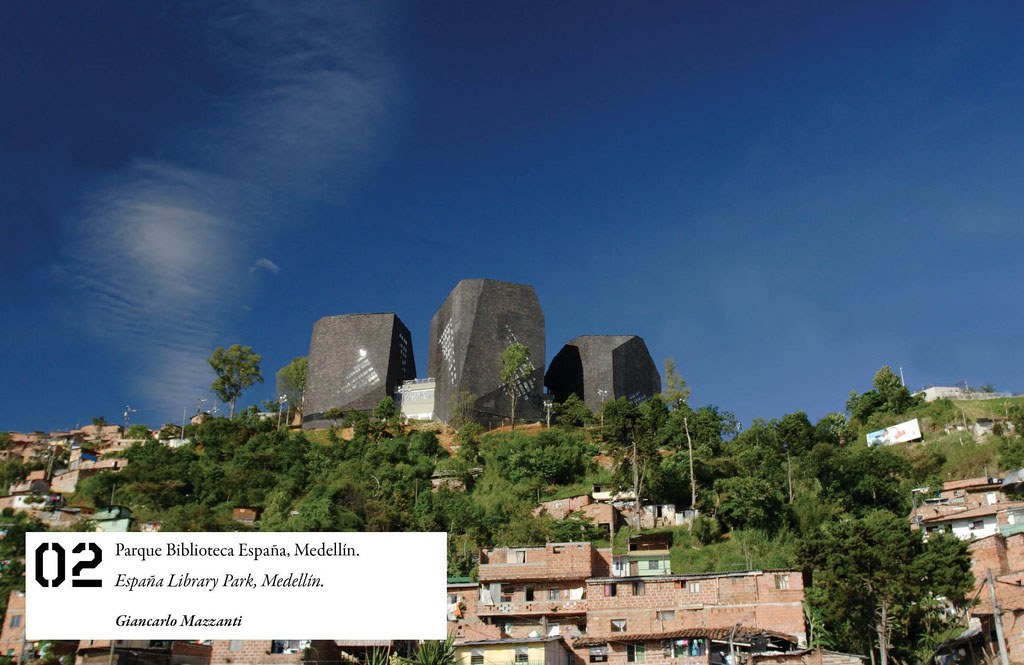

Giancarlo Mazzanti’s Parque Biblioteca España is located in the city of Medellín, home to more than 3.3 million residents and capital of the coffee-producing province of Antioquia. The city is situated in the Aburrá Valley of the Andes Mountains, in the geographically diverse country of Colombia. Medellín runs the length of the Aburrá Valley, extending fingers and palms up steep slopes to the ridges that contain and proclaim its identity as a highland haven and, per the prevailing weather conditions, the City of Eternal Spring. Its unique geographic qualities allow the entire span of Medellín to be seen from the surrounding mountain ridges; conversely, these ridges can be seen from any point along the river bisecting Medellín’s core, the Rio Medellín. Along Medellín’s western slope in the Santo Domingo Savio barrio sits the Parque Biblioteca España, articulating through its rough-hewn envelope the city’s mountainous boundaries – a distinct point of pride for its inhabitants.

Image courtesy of Giancarlo Mazzanti

Image courtesy of Giancarlo Mazzanti

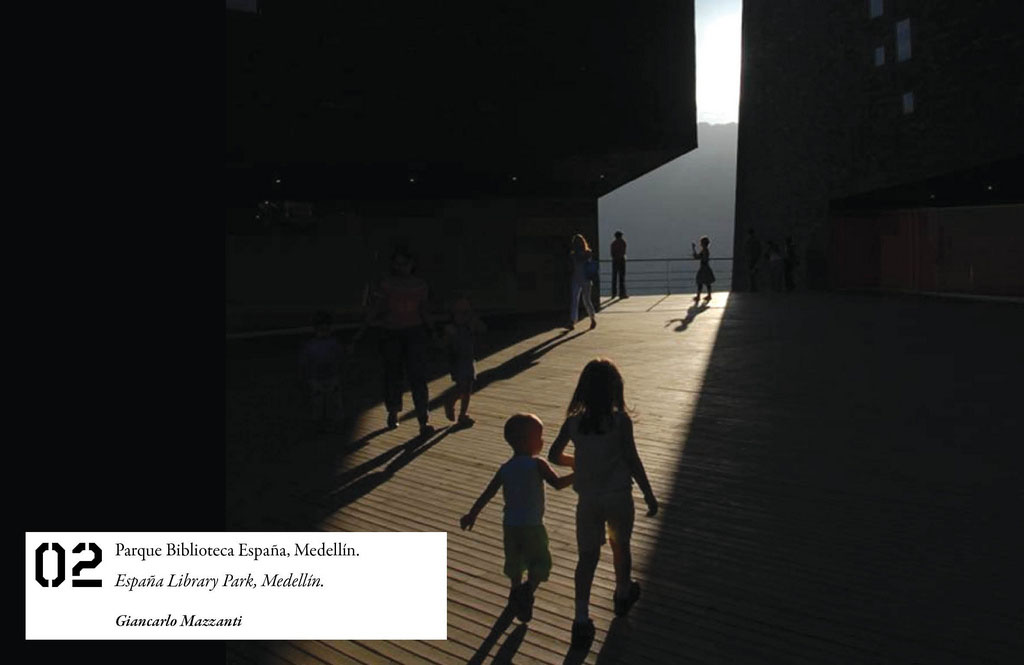

The Library Park – a typology the world at large could use more of – consists of three multi-storied cubes connected by broad rectilinear planes of public space, together housing an auditorium, a library, and a community center. The skin of the buildings is a rich, dark stone tile, lightly glossed and perforated to provide an even ambient light to its poured-in-place concrete core through a ring of skylights; the jagged void that begins at the concrete core and ends at the steel framing of the building’s envelope maintains a soothing visual continuity. The 11,500 sq. ft. project also includes computer stations, multiple spacious reading rooms, events space for local organizations, and even a day care – although it is primarily its stunning vantage point, offering panoramic views over the long declivity into the city’s heart, that attracts tourists national and beyond.

Aesthetically, the three dark masses among the ramshackle sprawl of unfinished cinder block and brick announce Biblioteca España as an intriguing and entirely unexpected manifestation of high culture in a locale most assuredly beyond the borders of Medellín’s wealth. Indeed, the Santo Domingo Savio barrio is beyond the reach of even the more basic social amenities, because its difficult terrain relegates it to the poorest and most historically disenfranchised sector of Medellín society; one could equate this area to the notorious Favelas of Brazil.

Rising high above the irregular roofs of this self-built community, the Biblioteca España stands “like a challenging manifestation of culture in a location of hope and uncertainty” as Mazzanti said upon the completion of the construction of the $4 million project in 2007.

To its creators and users, the Biblioteca España is much more than a pleasing modern exterior – it is the crux of a new paradigm of development aiming to advance a tangible frontier of proletariat empowerment. A sort of social siphon, it accordingly presents to the masses new avenues of personal and professional advancement via state-funded, institutional support: it offers educational seminars, workshops, and even a micro-finance center, which locals hope will remain the standard in years to come. It has thus been applauded as a cogent response to unacceptable living conditions and furthermore as an edifying construct, in its capacity to elevate active and even passive users beyond crime and depravity as their only means of earning a living. As much as it is vehicle and tool, this project has become a symbol of hope and point of pride for the city at large.

“The first step toward quality is the dignity of the space, and its way of showing another path.” – Giancarlo Mazzanti

The primary individuals driving this project were Mazzanti and the Mayor of Medellín in 2005, Sergio Fajardo. The Parque Biblioteca España is a shining example of Fajardo’s progressive and idealistic approach to raising the quality of life in Medellín’s most troubled neighborhoods and is an essential part of his master plan for social development. Fajardo’s plan was an attempt to repair the damage resulting from Colombia’s decades-long conflict with disruptive narcotrafficking regimes. So compromised was the social fabric of the Santo Domingo Savio barrio that allegedly the police entered it rarely, if at all. The scale of the drug conflict in Medellín earned it the pseudonym Murder Capital of the World for the latter days of the 20th century. Now, although much of the city remains impoverished, efforts like this are making a notable impact in turning Medellín from a symbol of fear to one of hope. As part of the same program, a gondola line was installed in conjunction with the Library Park to provide district residents infrastructural access to the major job centers of the city – thereby allowing them to avoid the debilitating two hour descent by foot.

It is unfortunate that one of our most powerful and effective tools for social reform largely eludes the contexts most requiring it: “Architecture only makes sense to the extent that it is capable of producing well-being, whether it is environmental or social. If not, it has no meaning; it becomes a game of egos, shapes, and buildings,” aptly stated Mazzanti, in an interview with Fajardo regarding the Parque Biblioteca España’s capacity to powerfully influence its locale, which for the large part includes communities functionally stunted by their lack of infrastructure and education. The statement made by this building is one that has begun to disseminate beyond its immediate area and is rapidly gaining recognition – a testament that it is not just a viable way to raise the quality of life but something that is essential to a healthy society at large. The results since its construction have been impressive: reduced crime and the achievement of higher education and increased social mobility.

When asked if he thought architects should have a political position that translates into their projects, and if architects can promote democracy with their work, Fajardo replied in effect that without a political position, then architecture would lose its connection to the community. From a conceptual angle, this connection is a social boon – while its physical tie is its tasteful and bold articulation of local landscape as identity.

“The first step toward quality is the dignity of the space, and its way of showing another path,” Mazzanti says. Beyond being an astounding achievement of aesthetic sensibility, the Biblioteca España is an extraordinary example of how public policy, city planning, and fostering social capital should converge to affect long-term systemic changes capable of advancing those that need it most.

Carlos Arango

A graduate of the Knowlton School of Architecture at The Ohio State University, Carlos is an avid life enthusiast who advocates adapting relics of the past to templates for the future. He is a strong believer in low-tech, long-term solutions for the predicaments of our current control-z, patch-and-splint culture. As an interdisciplinary writer and designer, Carlos seeks to explore and shed light on creative alternatives in construction and concept that challenge the status quo – with the aim of increasing the efficacy of society at large – whatever the setting, within whichever established order.