Latino Urbanism: Transforming the Suburbs

As more Latinos settle into the suburbs, they bring a different cultural understanding of the purpose of our city streets. Learn how the Latin American approach to street life is redefining "curb appeal."

Latin American streets are structured differently than streets in the United States, both physically and socially. Street vendors, plazas, and benches are all part of the Latin American streetscape. Traditional Latin American homes extend to the property line, and the street is often used as a semi-public, semi-private space where residents set up small businesses, socialize, watch children at play, and otherwise engage the community.

To create a similar sense of belonging within an Anglo-American context, Latinos use their bodies to reinvent the street. Few outward signs or landmarks indicate a Latino community in the United States, but you know instantly when you’re in one because of the large number of people on the streets. Street life is an integral part of the Latino social fabric because it’s where the community comes together. Street life creates neighborhood in the same sense that the traditional Plaza Central becomes the center of cultural activity, courtship, political action, entertainment, commerce, and daily affairs in Latin America. Lacking this traditional community center, Latinos transform the Anglo-American street into a de facto public plaza.

The numerous, often improvised neighborhood mom-and-pop shops that line commercial and residential streets in Latino neighborhoods indicated that most customers walk to these stores. The streets provide Latinos a social space and opportunity for economic survival by allowing them to sell items and/or their labor. Latinos have ingeniously transformed automobile-oriented streets to fit their economic needs, strategically mapping out intersections and transforming even vacant lots, abandoned storefronts and gas stations, sidewalks, and curbs into retail and social centers.

Street vendors add value to the streets in a Latino community by bringing goods and services to people’s doorsteps. The ephemeral nature of these temporary retail outlets, which are run from the trunks of cars, push carts, and blankets tossed on sidewalks, activates the street and bonds people and place. Enriching the landscape by adding activity to the suburban street in a way that sharply contrasts with the Anglo-American suburban tradition, in which the streets are abandoned by day as commuters motor out of their neighborhood for work and parents drive children to organized sports and play dates.

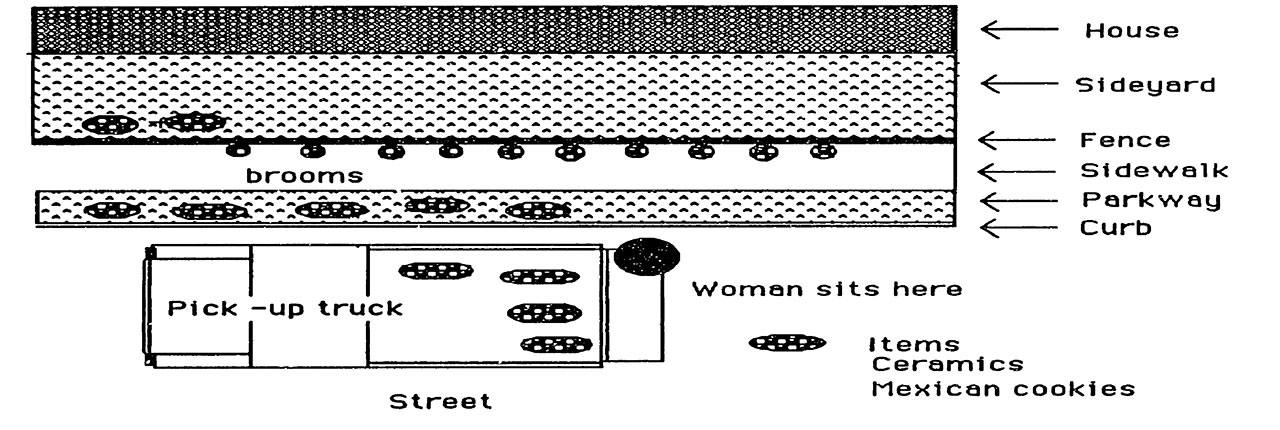

Weekend and some full-time vendors sell goods from their front yards. Fences are an important part of this composition because they hold up items and delineate selling space.

Weekend and some full-time vendors sell goods from their front yards. Fences are an important part of this composition because they hold up items and delineate selling space.

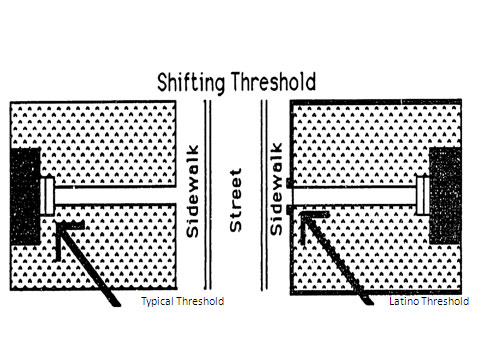

The use of fences in Latino neighborhoods transforms and extends the family living space by moving the threshold from the front door to the front gate. The front yard acts as a large foyer and becomes an active part of the “housescape.”

Graphics, Not Just Graffiti

Just as the streets scream with activity, leaving very few empty places, the visual spaces are also occupied in Latino neighborhoods. From vibrant graffiti to extravagant murals and store advertisements, blank walls offer another opportunity for cultural expression. The use of paint helps Latinos to inexpensively claim ownership of a place. The abundance of graphics adds a strong visual element to the urban form. Buildings are kinetic because of the flamboyant words and images used. Many buildings are covered from top to bottom with graphics. Murals can be political, religious, or commercial.

Here a front yard is transformed into a plaza, with a central fountain and lamppost lighting.

Here a front yard is transformed into a plaza, with a central fountain and lamppost lighting.

Fences and Good Neighbors

In many front yards across the United States you will find a fence. Most people build fences for security, exclusion, and seclusion. Latinos build fences for these same reasons, but they have an added twist in Latino neighborhoods. Waist-high, front yard fences are everywhere in the Latino landscape. The fences function as way to keep things out or in, as they do anywhere, but also provide an extension of the living space to the property line, a useful place to hang laundry, sell items, or chat with a neighbor. Fences represent the threshold between the household and public domain, bringing residents together, not apart, as they exchange glances and talk across these easy boundaries in ways impossible from one living room to another.

One woman on Lorena Street, in East Los Angeles, parked a pickup truck on the side of her house on weekends to sell brightly colored mops, brooms, and household items. Between the truck and the fence, she created her own selling zone.

By extending the living space to the property line, enclosed front yards help to transform the street into a plaza. This new type of plaza is not the typical plaza we see in Latin American or Europe, with strong defining street walls and a clearly defined public purpose. It is an unconventional and new form of plaza but with all the social activity of a plaza nonetheless. In the United States, however, Latino residents and pedestrians can participate in this street/plaza dialogue from the comfort and security of their enclosed front yards.

Wherever they settle, Latinos are transforming America’s streets. Peddlers carry their wares, pushing paleta carts or setting up temporary tables and tarps with electrifying colors, extravagant murals, and outlandish signs, drawing dense clusters of people to socialize on street corners and over front yard fences. Where available, Latinos make heavy use of public parks, and furniture, fountains, and music pop up to transform front yards into personal statements, all contributing to the vivid, unique landscape of the new Latino urbanism.

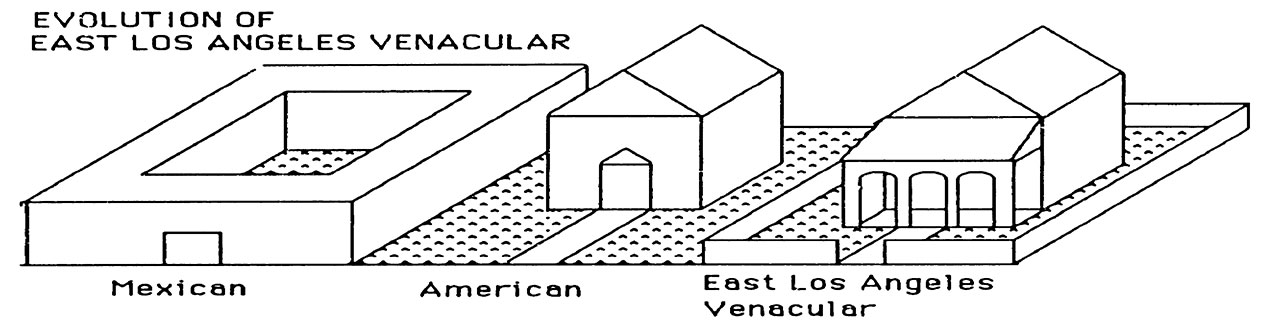

The new Latino urbanism found in suburban Anglo-America is not a literal transplant of Latino American architecture, but it incorporates many of its values. The homes found in East Los Angeles, one of the largest Latino neighborhoods in the United States, typify the emergence of a new architectural language that uses syntax from both cultures but is neither truly Latino nor Anglo-American, as the diagram illustrates.

James Rojas

James Rojas is an urban planner, community activist, and artist. He is one of the few nationally recognized urban planners to examine U.S. Latino cultural influences on urban planning/design. He holds a Master of City Planning and a Master of Science of Architecture Studies from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His influential thesis on the Latino built environment has been widely cited. Growing out of his research, Mr. Rojas founded the Latino Urban Forum (LUF), a volunteer advocacy group, dedicated to understanding and improving the built environment of Los Angeles’ Latino communities. Currently he founded Placeit as a tool to engage Latinos in urban planning.