Optimum Value Engineering

"Optimum value engineering" gets you the biggest bang for your construction buck. Learn how to use common sense and weigh your goals against your options to apply this thrifty approach to your next project .

Image courtesy of Fernando Pagés Ruiz

Image courtesy of Fernando Pagés Ruiz

The catchall term “value engineering” describes a studied approach to reducing building costs without compromising quality. Value engineering entails comparing a range of construction methods and materials to determine the most cost-effective means of obtaining a desired structural, aesthetic, or durability standard. Energy efficiency, whereby project teams work toward optimal comfort and utility while lowering operational costs long-term, is an excellent example of value engineering.

This cost-oriented design tactic originated in manufacturing at General Electric (GE) by Lawrence D. Miles during World War II, when supply shortages forced GE to find substitute materials to produce certain military supplies. The stand-ins, such as steel alloys, often led to better products at reduced costs. After the war, GE pursued this approach in their commercial lines. Other industries followed suit and, by the early 1970s, the value engineering approach finally came to the construction industry.

Many of today’s green technologies, such as advanced framing and right-sized heating and ventilation systems, actually derive from cost-cutting efforts pioneered in the 1970s. By definition, material-sparing techniques not only help conserve natural resources, they can help conserve a budget, too.

Some of the best examples of value engineering in construction come from tract home developers, whose operations resemble manufacturing because they build a finished product and then sell it on the open market. General contractors sell a service; they have a client to cover cost overruns, often with additional markups. Tract home developers make their money on the slim margin between cost and market value.

This is why tract home developers have always been the most aggressive in applying value engineering to construction, sometimes setting up value-engineering departments that focus on nothing but lowering costs. This is also why many developers keep the design process in house, rather than employ outside design firms, approaching every stage of a project, including design, with the intention of optimizing value.

Some developers call this affordability-by-design approach the “front-loaded” method. Instead of working backward to save money on a desirable floor plan (the lowest bid approach), they start by sketching the very first draft of a plan using a palette of value-engineering options that assures efficiency. Although this method usually focuses on economy as the primary goal, it doesn’t preclude architectural creativity, durability, or efficiency as part of the “value” equation.

The word "value" in this context describes a goal. For example, the value may come with achieving LEED Platinum certification. The value-engineering process would entail analyzing every design, specification, and construction method chosen with an eye to finding the least costly means to achieve this certification. In other words, value engineering is not a synonym for cheap building – it means reducing costs while completing the construction in the best way.

Keeping a real-world lid on construction costs requires weighing many options and consumes a lot more time than architecture as usual. The value portion of the equation helps keep the focus on specific design criteria, avoiding design creep, discarding otherwise attractive design elements that cost too much while not advancing the value equation forward. The engineering portion entails studying the options, sometimes fully designing and pricing several approaches before deciding which one represents the lowest cost means to a desired end.

For example, if you can achieve an energy-efficiency goal by either increasing insulation values or heating equipment efficiency, you would design and price the structure both ways, including all related impacts, such as the deeper wall cavities required for more insulation and even the larger trim required for the doors and windows in those thicker walls and extra drywall and paint, in addition to the added cost of more insulation. Then compare this fully extrapolated cost to the similarly extrapolated cost of higher-efficiency equipment. I make this sound complicated and somewhat taxing because it is: truth be told, my example is a simplification.

Think Inside the Box

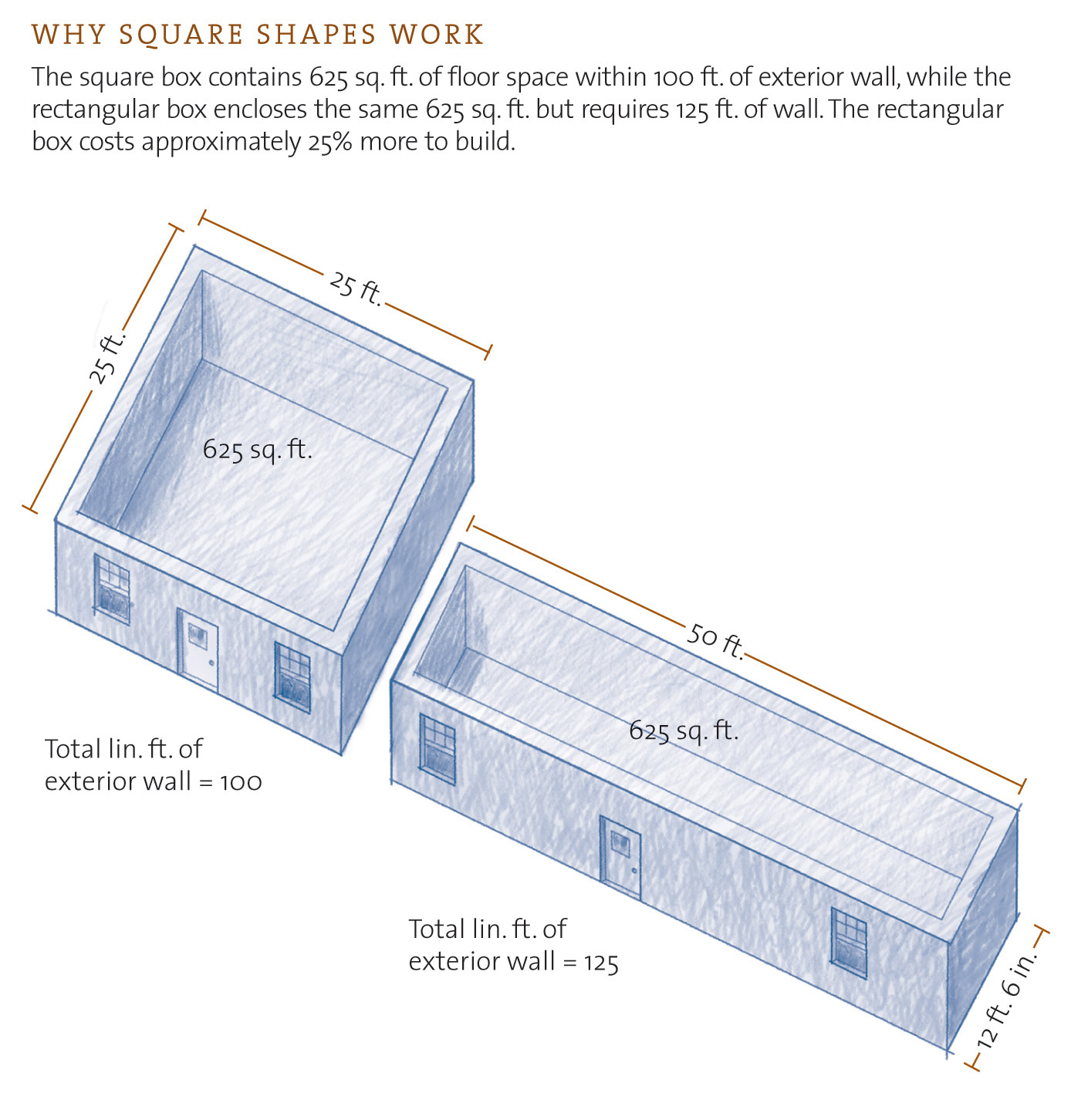

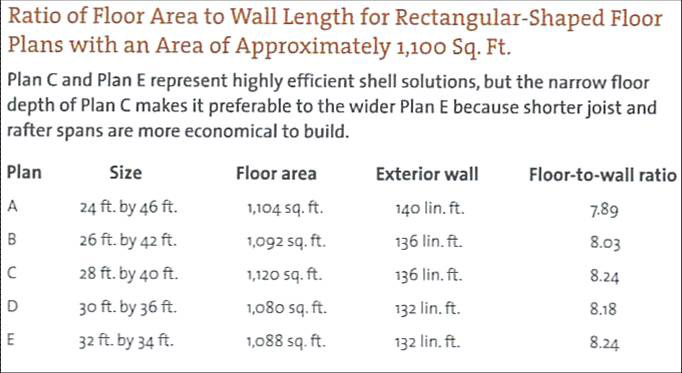

Have you ever wondered why tract homes look boxy? The basic “box” of low-cost design goes back thousands of years and reoccurs in every age. Frank Lloyd Wright was a proponent of the modular box in his Usonia Homes, meant to be affordable. This shape works so well in construction because it yields the highest floor-to-shell ratio. In other words, it provides the smallest area of exterior surface to cover a given living space. Exterior surfaces with siding, weather barriers, and insulation represent an expensive component. They also represent weather exposure, which is why this most basic trick of designing low-cost structures as a small square or, for larger structures, a rectangle doubles as the most energy-efficient design strategy.

To understand this concept, picture an imaginary square house of only 625 square feet with four 25'-long exterior walls. This simple structure has a floor-to-wall ratio of 1.28 (the number of square feet of 8' exterior wall that it takes to enclose each square foot of interior floor). Now picture the same 625 square feet of living space enclosed within a rectangular footprint of 12.5 by 50 linear feet. This structure has a floor-to-wall ratio of 1.60 – a whopping 25% drop in efficiency. By limiting the total area of exterior wall, the box eliminates the additional foundation, framing, insulation, siding, and other components that make exterior walls an expensive element.

Case Study: Centex Homes of Dallas, Texas

Over a period of five years Centex Homes, one of the nation’s top ten homebuilders, applied value-engineering methods to save over one billion dollars.

They did it by:

-

Actively seeking input from suppliers and contractors;

-

Red-lining to perfection;

-

Improving communication with contractors and suppliers, to avoid mistakes;

-

Focusing on unit pricing of material and labor;

-

Splitting purchasing into materials and labor and avoiding turn-key operations whenever possible;

-

Avoiding over-engineering;

-

Challenging suppliers and contractors to justify increases; and

-

Scheduling aggressively to shorten cycle time.

This made it possible for Centex to:

-

Reduce the structure cost of their homes from 60% to 50% of sales price,

-

Lower direct construction costs by nearly $8,000,

-

Negotiate $800 per home in rebates, and

-

Reduce the cost of callbacks by $1,000 per home.

Source: Randy Luther, Vice President of Construction Technology, Centex Homes

Fernando Pages Ruiz

Homebuilder, developer and author Fernando Pagés Ruiz builds in the Midwest and Mountain States and consults internationally on how to build high-quality, affordable and energy-efficient homes. As a builder, his projects have numerous awards including the 2008 “Green Building Single Family House of the Year” and the 2007 “Workforce Housing Award” from the National Association of Home Builders. In 2006, the Department of Housing and Urban Development's PATH project chose him to build America's first PATH Concept Home, a home that is affordable to purchase and to maintain while meeting the criteria of LEED for Homes, ENERGY STAR, MASCO Environments for Living, and the NAHB's Green Building standards. A frequent contributor to Fine Homebuilding and EcoHome magazines, Pagés is also the author of two books published by the Taunton Press: Building an Affordable House: A high-value, low-cost approach to building (2005) and Affordable Remodel: How to get custom results on any budget (2007).

Contact Fernando on facebook or by way of his website buildingaffordable.com.