Building the Better Block: New Urbanist Guerrilla

Patience has never been a virtue of the young. Change is. But change has always come at a glacial pace and an exorbitant price when it involves land development. The dreaded bureaucracy of planning departments and city councils can chew up more time over debating a project than it takes to build it. No longer. What would normally take years of design and debate, a new guard of young, idealistic urban activists, including Jason Roberts, a self-described artist and computer consultant, and partner Andrew Howard, A.I.C.P. of Team Better Block, now accomplish overnight – or, at most, in 72 hours.

Using Greenpeace-style, urban-guerrilla tactics and an army of volunteers with fresh ideas, paint, and movie props, Roberts and Howard transformed one block in their Dallas neighborhood to showcase what could be, if citizens, instead of zoning boards, could have it their way. The “punk rock” street improvement, as Roberts describes Team Better Block’s first foray into guerrilla urbanism, skirted local ordinances but argued so convincingly on behalf of people-friendly redevelopment that Roberts and Howard enjoyed full municipal backing for Team Better Block's subsequent projects.

Building the Better Block

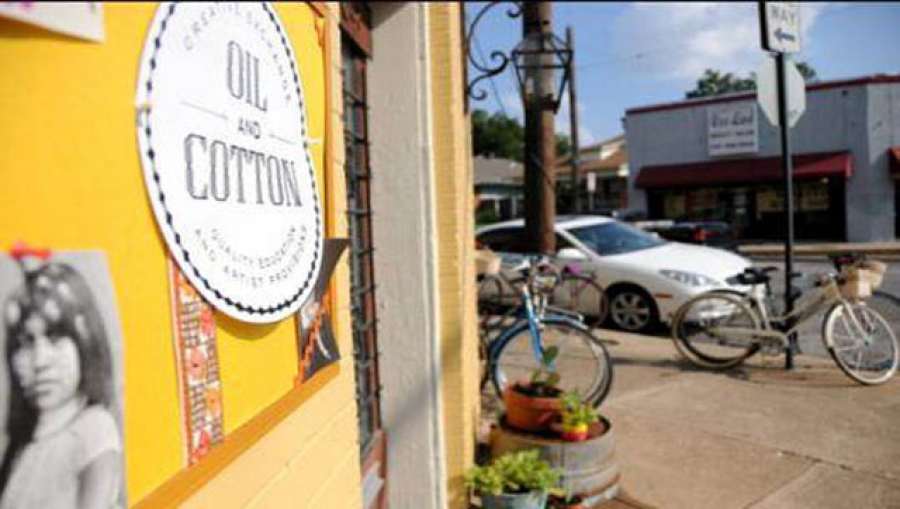

The weekend pilot project that propelled a New Urbanist Guerrilla movement to national attention occurred on a highly forgettable commercial strip in the Dallas suburb of Oak Cliff, Texas. A group of community activists, organized by Roberts and Howard, assembled a willing cohort of neighbors and sympathizers to transform one city block.

First, they approached the owners of several abandoned buildings along the strip and obtained access to set up temporary businesses. They met with community groups and local entrepreneurs who had ideas on what businesses might appeal to the neighborhood. They recruited volunteers and asked for donations of any sort, including tables, chairs, potted plants and small trees, stage props, port-a-potties, and paint. They studied the streetscape and loosely planned the redesign.

One Friday evening in April 2010, under the banner of the Better Block, volunteers showed up at a tired segment of Tyler Street with a truck full of plants, props, and people power. They worked through the night and installed a temporary café with outdoor seating, including pump-carafes and pastry donated by a local baker; they created a children’s art center so that families with children could participate; they set up a gift store featuring local artists; and, thanks to a successful book drive, they gathered enough tomes for small used book stand. They offered as many local products as possible, from fruit to furniture. They brought in planters and laid out donated greenery to divide and screen the street; they brought in temporary streetlamps for lighting. They strung wires from cornice to cornice and hung Christmas lights for ambiance. They painted a cycling lane along the curb and striped parking stalls. They reduced traffic from four lanes to one.

They also put up a sandwich board listing all the municipal ordinances they had to break to get the job done, including prohibitions on fruit stands and outdoor café seating. And then they invited the local authorities. “We invited the city council and zoning staff, and we thought -– whoops – we’re going to get in trouble,” says Roberts. Instead, one city council member was overheard asking, “Why do we have all these ordinances anyway?” The next day, Team Better Block had a seat at the decision-making table, advising the city on plans to revitalize the streets of Dallas.

Ross "Build a Better Boulevard" Challenge

Team Better Block's Ross Better Boulevard project rebalanced the equation of the street, giving equal weight to people and cars. This simple measure dramatically changed the psychology of the street and showed the potential for how Dallas can move forward in creating great places. Read more...

Better Block II

The 1300 Block of West Davis Street (Dallas) was the location of the second Better Block project. Team Better Block transformed a gray, concrete, and car-focused block and converted it into a more humane space that placed people first. Read more...

A YouTube video (shown above) of the event went viral, gaining the project national recognition. The storefronts along Tyler Street are no longer vacant. The temporary children’s art school has become permanent. Roberts and Howard quit their corporate gigs and now devote their time to organizing Better Block events, including their recent 72 Hour Challenge, sponsored by the City of Dallas, challenging citizen teams to remake a high-profile section of Dallas’s Ross Avenue from Pearl Street to Washington Street into a “welcoming, comfortable, and vibrant boulevard.” The next big bash, Better Block Philly, is slated for mid-October in Philadelphia. Roberts and Howard consult and offer online training to help other cities build their own versions of a better block.

Come and They Will Build It

Indeed, cities from San Francisco to San Antonio are marshaling the talents of local entrepreneurs, architects, and bona fide artists, as well as professional designers, to take redevelopment from the lofty master plan approach and return it to the gritty street level. In place of the traditional, two-dimensional drawings designed and defended by high-price consultants, citizens conceive and then create life-size maquettes.

For example, the City of Buffalo, New York, laid out hundreds of Adirondack chairs on a wharf and empty lot in an underused waterfront and then invited food carts and pop-up retail tents to test whether a new, waterfront entertainment district would actually draw a crowd – it did. Citizens organized the event with the help of planners, bringing about their vision for the waterfront along with a critical mass, proving the market before attempting to land anchor tenants in a new twist on “build it and they will come.” Come on down, and then they will build it.

New York used a similar approach to establish a pedestrian mall at Times Square. In 2005, the city sponsored a coalition between nonprofit planners Project for Public Spaces (PPS) and New York-based cycling advocacy group Transportation Alternatives. The partners were tasked with facilitating changes to achieve a better balance among motor vehicles, pedestrians, and bicycles along New York City streets.

Early in this project, the coalition evaluated pedestrian versus vehicle patterns at Times Square and found the pedestrian space lacking. They recommended short-term changes that would improve Times Square’s utility as a destination rather than a motor vehicle corridor. In an urban planning version of the scientific method, they ran an experiment to test the hypothesis: New York City’s Department of Transportation (NYC DOT) agreed to temporarily close some traffic lanes and convert them to pedestrian use. The Bloomberg administration set out rubber folding chairs, converting vehicle lanes to lounge chair lanes for people to sit, chill, and meet one another. The public reaction was a big thumbs up and NYC DOT expanded the program to more than 20 blocks. They added movable tables, umbrellas, and other amenities. Mayor Bloomberg decided to make the changes permanent, and New York City will soon reconstruct the temporary plazas and corridors using high quality materials designed to be permanent.

Start With Petunias

According to Ethan Kent, Vice President of PPS, cities have traditionally sought catalyst projects, such as a major retailer, a museum or an events center, hoping that the gravitational pull of a major investment would spur economic development around it. Many of these projects have failed miserably, says Kent. The informal development process embodied in efforts such as the Better Block, the Buffalo Waterfront, and Times Square have gained popularity, in part because of the recession. Strained municipal budgets and overextended developers hesitate to speculate on major developments. The low-cost, incremental approach provides a way to tiptoe into the future instead of diving in headfirst. PPS likes to describe the process as, “Start with the petunias.” in other words, start with the easy stuff (i.e., planters, paint, benches, and music), the things that attract people and create a sense of place.

Kent suggests that the key elements of any successful public space include easy access, engaging activities, hang-out-inducing comfort, and, most of all, the opportunity for high levels of sociability. His firm has become expert in proposing small, tactical steps to cultivate a sense of place and to postpone the big, top-down projects for later, or maybe never. They brand this approach "Lighter, Cheaper, Quicker." “Instead of using a whole lot of money on transformation, make smaller changes and get the same economic and social benefit,” says Kent. If success proves the method, the approach must work. “We have completed successful in all 50 states and 42 countries,” says Kent of the organization his father founded in 1975.

Crowd Source Planning

Private developers have also taken notice and started to “crowd source” design and “screen test” their development concepts, says Kent. This bottom-up approach not only provides market safety but sometimes reveals surprising opportunities. Recently, a master developer working with the City of Bristol, Connecticut, wanted to construct a piazza to anchor a large commercial project. PPS helped to create a temporary, one-summer piazza pilot project on the proposed development site, a failed mall. They invited food trucks, set up beach umbrellas and loungers, bales of hay, kids' games, outdoor movies, and a summer-long music festival to showcase the site. During the event, PPS and the developer surveyed participants in person and online and asked them what they wanted in the area. Besides the usual coffee shops, jazz pubs, and art galleries, the developers were surprised to discover strong demand for a bowling alley, antique store, and art movie theater – all of which eventually became part of the Bristol Piazza development plan.

“We need fewer think-tanks, and more Do-Tanks.”

Aurash Khawarzad, Senior Planner with PPS

This informal process, which Kent prefers to describe as “Tactical Urbanism” rather than the more bellicose-sounding, “Guerrilla Urbanism,” is fast becoming the municipal planning equivalent that Wikipedia has become to encyclopedia publishing and YouTube has become to video production. To wit, PPS, a nonprofit organization, obtains some of its project funding and financing at kickstarter.com. Of course, in going mainstream, the approach risks losing some of its vitality. Once Team Better Block started working under the auspices of Dallas, the process grew bulkier. Some PPS employees have even started community action groups outside the organization's framework to keep the spirit of innovation alive, including “East New York Farms!” a coalition of female, Caribbean farmers employing neighborhood youth to learn agricultural skills and sell produce at the farmer’s market. As Aurash Khawarzad, a Senior Planner with PPS, remarks, “We need fewer think tanks and more 'do tanks.'”

“The old way of planning got stuck in a rut of brainstorming and intellectual masturbation,” says Khawarzad. “Every movement needs a new injection of ideas. We have new problems and new tools, and we know these tools. The ... old way does not work fast enough, and we cannot measure success from the top. It’s the effect on the ground level where we should measure our success.”

Fernando Pages Ruiz

Homebuilder, developer and author Fernando Pagés Ruiz builds in the Midwest and Mountain States and consults internationally on how to build high-quality, affordable and energy-efficient homes. As a builder, his projects have numerous awards including the 2008 “Green Building Single Family House of the Year” and the 2007 “Workforce Housing Award” from the National Association of Home Builders. In 2006, the Department of Housing and Urban Development's PATH project chose him to build America's first PATH Concept Home, a home that is affordable to purchase and to maintain while meeting the criteria of LEED for Homes, ENERGY STAR, MASCO Environments for Living, and the NAHB's Green Building standards. A frequent contributor to Fine Homebuilding and EcoHome magazines, Pagés is also the author of two books published by the Taunton Press: Building an Affordable House: A high-value, low-cost approach to building (2005) and Affordable Remodel: How to get custom results on any budget (2007).

Contact Fernando on facebook or by way of his website buildingaffordable.com.