Know Your Vocabulary: Passive House vs. Active House

Video

Houses are stationary objects, so using terms like “passive” and “active” to describe them initially seems a little odd. These terms actually embody design strategies that create comfort for occupants while drastically cutting down on energy use.

Credit: Normann Sloth

Credit: Normann Sloth

Passive vs. Active

Active elements generally use or process electricity or another fuel. Air conditioners cool, while furnaces heat. A flick of a light switch illuminates an interior space. A more eco-friendly approach involves the installation of solar panels to actively capture sunlight and convert it to electricity to power your home.

Passive strategies, on the other hand, take advantage of nature – specifically the sun and wind – to achieve comfort. This common-sense approach builds on traditional methods that have been used in residential design for centuries. The first tenet of passive design is site orientation. A home should be positioned to take advantage of the path of the sun; for example, southern-facing glazing is ideal for certain climates because it captures indirect light throughout the course of the day.

In the summer, it is necessary to block sunlight to keep your house cooler. Passive strategies, such as planting shade trees or designing overhangs, can provide relief. Overhangs should be positioned to block summer sun while allowing lower-angle winter rays to penetrate and heat your house. Natural ventilation also takes some strain off mechanical systems. Besides the benefit of allowing fresh air to circulate, operable windows and skylights create a cross-breeze and lower the temperature of your home by several degrees.

Another key element contributing to the energy efficiency of passively designed homes is properly insulated walls and roofs. Additionally, a well positioned thermal mass – a thick concrete or masonry wall – can absorb heat from the sun throughout the day and warm your home at night, maintaining a consistent and comfortable interior temperature.

Certifications and Standards

Want to make it official? Follow Passive or Active standards targeted at homes that embrace the respective strategies.

Passive House

Although natural ventilation plays a role in passive design, a certified Passive House relies on air-tightness to achieve optimal thermal performance. The Passive House movement, called Passivhaus in Germany where it was founded by Dr. Wolfgang Feist in 1996, has since spread to many countries, although it’s been a little slow to catch on in the United States – only around 20 houses have been certified here.

A certified Passive House features walls and a roof packed with significantly more insulation than the typical house, as well as thermal breaks to further prevent heat loss or gain. These homes often incorporate triple-pane windows instead of the standard double-pane versions. Dennis Wedlick, AIA, who designed the Hudson Passive Project, the first certified Passive House in New York State, has likened the design approach to that of a thermos or cardboard coffee cup: surface area is minimized, a sleeve provides a thermal break, and the act of stacking cups results in a higher insulative value.

Of course, a structure can become too air-tight, resulting in “sick building syndrome.” Passive Houses rely on a heat-recovery system to exchange stale for fresh air and eliminate mold-causing moisture. Aside from these small but technologically advanced boxes, Passive Houses are decidedly low-tech. They don’t need an air conditioner or furnace, eliminating most ductwork. In fact, these homes exhibit a heating load reduction of 90% over traditional construction. They can hold onto heat from the sun or even heat emitted by bodies of the occupants. You can still open the windows for natural ventilation, if desired.

The drawbacks? Passive Houses typically cost more upfront than traditional construction, often upward of 10%, although proponents argue that homeowners quickly recoup the costs in energy savings. Such upfront costs are spent on beefier materials like the triple-pane windows, which unfortunately are not widely available in the United States and must be shipped from Europe, negating some of the "greenness." In many cases, homeowners still rely on mechanical systems as back-ups; although Passive House proponents claim that its strategies work in all climates (even a research station in Antarctica), some designers have found it difficult to meet the standards in extreme climates.

Active House

Though it might sound as if an Active House is the complete opposite of a Passive House, the strategies are not actually at odds with one another. Active Houses follow passive design techniques but take them to the next level by producing their own energy, often via photovoltaic panels. More than a net zero house, an active house generates positive energy that can then be fed back into the grid.

Active House Example: Solhuset

Located in Hørsholm, Denmark, Solhuset will be Denmark's most climate-friendly nursery. Read more about the project here.

Active House Example: LichtAktiv Haus

Located in Hamburg, Germany, LichtAktiv Haus is a renovation of a of a traditional 1950s home. Read more about the project here.

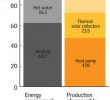

Although the Germans pioneered the Passive House and are great producers of solar panels, it is Lystrup, Denmark, that is home to the world’s first Active House. Aside from containing plenty of insulation and triple-glazed windows, this home is decked out with a solar thermal and solar electric system. A computer system regulates, monitors, and adjusts the home’s power use. The price tag? Nearly $800,000 – probably not feasible for most of us.

While there are currently no documented Active Houses in the United States, you can experience a Passive House firsthand, visit the PNC SmartHome Cleveland (as shown above) at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. It will be on view through the end of 2011.

Murrye Bernard

Murrye is a freelance writer based in New York City. She holds a Bachelor's degree in Architecture from the University of Arkansas and is a LEED-accredited professional. Her work has been published in Architectural Record, Eco-Structure, and Architectural Lighting, among others. She also serves as a contributing editor for the American Institute of Architects' New York Chapter publication, eOculus.

Website: www.murrye.com